Why Do Scientists “Cite” the Top 5 Regrets of the Dying?

It pops up in my Twitter feed quite often, it seems to me. A scientist will buttress their argument that academics shouldn’t work too much, with this claim: it’s the second top regret of the dying, they’ll say.

I don’t know whether I find this more fascinating or aggravating. I get aggravated because of the class issues. On the side of the tracks I came from, people have no choice about working too hard. They do it because they have to, and supporting themselves and their families is a profound source of lifelong pride and working class values, not something to ever regret. Wishing you could have pursued another kind of life, sure, but that was a privilege denied, not a decision.

Why do I find it fascinating? Because I think it’s obviously “woo”, and I wonder how it has persisted as though it’s factual. If you challenge someone on it, they come back at you as though this is data-based. I guess that’s because an influential newspaper article in 2012 described it this way:

A palliative nurse has recorded the top five regrets of the dying.

Okey dokey. So this week, after one too many of those tweets, I decided to dig into it. Let’s start with the source.

In 2011, Bronnie Ware published a book, and that newspaper article was follow-up publicity. The “top 5 regrets” thing came from a wildly successful post she wrote on a New Age-style blog called “Inspiration and Chai”. In the book’s blurb, Ware described herself this way:

…author, songwriting teacher, and speaker from Australia… Bronnie lives in rural Australia and loves balance, simple living, and waking up to the songs of birds…

…After too many years of unfulfilling work, “Bronnie Ware” began searching for a job with heart. Despite having no formal qualifications or experience, she found herself in palliative care…

Since then, her website shows, the top 5 regrets has grown into a business, of books and writing and workshops like this one coming up in Santa Cruz, in which, Ware says, you will:

Gain tools to pivot and avoid creating any new regrets; Master any concerns over end-of-life resolutions to live life boldly and head-on…Break through old patterning to fully align with the invaluable sacredness of your time and energy. Ground your life in an abundance of connection and the power of conscious intention. Return home with the practical insight to nurture a lighter spirit, clearer vision, and the real audacity to navigate your life into absolute joy, love, and fulfillment.

I haven’t read the book. Here’s a reader’s brief one-and-a-half star review:

Book club read, disappointing in that it’s more of a journal written by an Australian girl “finding herself” whilst working as a caregiver for ill people. Lots of stuff about herself, no scientific basis for the list of regrets. Easy read, though on the boring side; did manage to finish the book.

The original blog and post are on the Internet Archive. There’s no pretense that this is a study, no number of patients, no recording or analysis:

For many years I worked in palliative care. My patients were those who had gone home to die. Some incredibly special times were shared. I was with them for the last three to twelve weeks of their lives.

It’s pretty grim when you strip it down, with the apparent intention of convincing people they need help:

Most people had not honoured even a half of their dreams and had to die knowing that it was due to choices they had made, or not made.

The top 2 regret, wishing they hadn’t so worked so hard, came, she said, from “every male patient that I nursed”,

By simplifying your lifestyle and making conscious choices along the way, it is possible to not need the income that you think you do. And by creating more space in your life, you become happier and more open to new opportunities, ones more suited to your new lifestyle.

The signals for this being classic self-help/New Age philosophy were clear in that newspaper article – except, I guess, the part about the author not being a palliative nurse. And except for the implication that this was based on tallying something recorded. Still, if anyone thinks this was somehow data-based, they didn’t look very closely.

Now for the serious part. I’m genuinely interested in this. When I was about 13 or 14, it must have been, I saw the French crooner Charles Aznavour on TV performing the song, “Yesterday, when I was young”. It was something like this clip on YouTube. It didn’t seem the slightest bit corny to me. It made me weep. Later, I bought an album of his greatest hits – vinyl, in those days, and I played that song over and over.

I didn’t want to be that old person, full of regrets: non, rien de rien… I wanted to live the Édith Piaf take, a bold and rollicking life of mistakes and passion, and no regrets.

Clearly, the “top 5 regrets” does not come from any sort of scientific research. And I’ve read infinitely better philosophy and religious thinking on the subject. But what, I wondered, is in the psychological science scholarship on regrets at the end of life? Do we know, in any culture, about common regrets of the dying, and does class make a difference?

In 2007, Marcel Zeelenberg and Rik Pieters published a theory of regret regulation. Regret, they wrote, is choice-based: “Regret is a comparison-based emotion of self-blame, experienced when people realize or imagine that their present situation would have been better had they decided differently in the past”. They posit that “The more justifiable the decision, the less regret”.

Zeelenberg and Pieters said that research on regret boomed after 1990. Their article is a fascinating overview if you are interested in regret. I had always thought of my concentration on Aznavour’s message as an important life lesson – but reading this, I am pondering whether feeding my “regret aversion” was a good thing. This paper doesn’t help on the subject of common regrets at the end of life however.

Robert Neimeyer & co studied a group of people in hospice care, including the subject of regrets. They point to studies and examples in their own study suggesting if you have genuine life regrets, it can intensify suffering at the end of life. There are some poignant stories in this study. They don’t try to get at the question of common regrets, though. I didn’t find a study that did. Please let me know if you know of any.

Kara McTiernan and Michael O’Connell published a paper about people in palliative care in Ireland that helps put the concept of regrets at the end of life into perspective, I think. (Their methodology was interpretative phenomenonological analysis.) Life regrets weren’t a big feature of this phase of life for most people: people were trying to cope with physical issues, have a meaningful life, create a legacy, and deal with a variety of unfinished business in their lives.

Selma Rudert and colleagues came to a reassuring conclusion for the regret averse (2014 – manuscript PDF):

[A]t the end of their life people might be increasingly motivated to make this end appear as positive as possible and to believe that they have lived an overall meaningful life. Against this background, we speculate that at the end of their lives, people regret less than before.

Taken together, there is theoretical as well as empirical evidence that when the end of one’s life nears, people are motivated to believe that the things they could potentially regret are “too few to mention,” as Frank Sinatra put it in his song “My Way.”

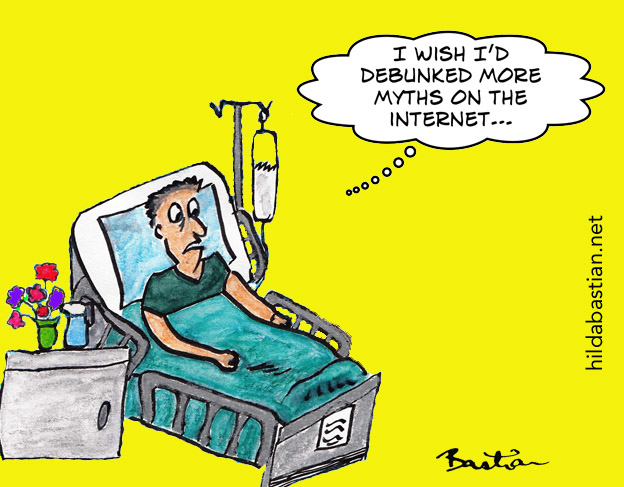

And what about the answer to the question in this post’s title? Why do scientists “cite” Ware’s top 5 regrets? I think many might be susceptible partly because of their social class, and partly because of either a lack of radar for psychobabble, or not thinking it matters. But mostly, I think it’s confirmation bias, and not being critical of a presumed evidence base that supports their beliefs. No one is immune to that. But if confirmation bias also leaks into what we promote in areas of scientific controversy, we’ll be damaging our credibility and claim on the public trust. Being more careful of what we put forward as factually-based generally is good practice.

And finally, in case you’re wondering, neither Aznavour nor Piaf are my go to songs on the subject of regrets these days. It’s Cochrane. No, not that one! Tom Cochrane:

I can’t stand and walk while you stand accused…

Remember the good times oh, least you forget…

After all the s**t you know we’ve been through

Oh, there ain’t a shovel big enough in the world

That can move it…

Remember who you are, and don’t you forget

Oh, and have no, no regrets…

~~~~

Possibly also of interest on this blog:

Post-Truth Antidote: Our Roles in Virtuous Spirals of Trust in Science

Disclosure: I, too, live in rural Australia, love balance, the simple life, and waking up to the songs of birds. I spent a serious chunk of my early adulthood hippie-adjacent, but the social class aspects of New Age spiritualism broke my initial attraction to it.

This post is not intended as a defense of workaholism. See for example my posts on the subject of vacation.

The cartoons are my own (CC BY-NC-ND license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

DOES “HUMAN NATURE” EVOLVE TOO?

This goes in the direction of Steve Moxon’s belief that culture reflects human nature. But can we go a step further?

By Bruce Lepper (a few years ago when the Human ethology list was in its heyday))

Hilda Bastian says :

If you have a very strong prior existing

belief, chances are it’s going to exert a strong

bias on how you select and react to evidence on the subject.

In my view this doesn’t only affect those who have “very strong beliefs”. It is a continuous process that affects all humans. We select subjects and activities which fit our personalities and environments, but not only that, we also select evidence that fits. In this way, the direction of evolution of mainstream science follows the needs and desires of the most common “researcher personality”, subject to environmental conditions.

Of course, there is no such thing as the “researcher personality”, but (if we understood more about personality) the majority of those attracted by scientific research could probably be shown to be emotionally different from those more attracted by, for example, commercial or military occupations.

From time to time a particularly dedicated researcher like Darwin with his or her own special personality needs and desires makes a major breakthrough, opening up new possibilities of research. The very fact that the now glaringly obvious theory of evolution wasn’t noticed until the end of the 19th century, and is still not accepted by 1 in 3 educated Americans, is more evidence that it wasn’t a subject that fitted very well with human nature’s (and human culture’s) needs and desires.

Thanks to Darwin and others we are now stuck with this embarrassing subject. There’s no going back in science (if we’re lucky). However, our mainstream researcher nature will only pursue the “best fit” parts of the theory, and the odd-guys (I was going to say non-conformists, but they are just doing their thing, they are not really interested in what the majority thinks) will be severely tackled unless they can produce book-fulls of obvious evidence and even then on condition that their conclusions don’t run too counter to our mainstream human needs and desires.

The under-estimated cultural influence on research is enhanced in a connected world. Ironically, at the same time as scientific information is vastly more accessible, so are the repercussions of investigating subjects which run counter to common cultural ethics. Jay Feierman and others know they are treading a delicate path investigating the ethology of religion. But the factor that is even more under-estimated is the cognosphere* of the researcher, born into an evolving culture and environment that influences the subjects that his own particular personality finds “interesting”, subjects that he or she will be unconsciously striving to develop throughout their lives.

Bruce

*cognosphere

Well yes, sorry, I had to invent a word for this:

cognosphere: (n) The sum of genetically and culturally derived components influencing a thought process in an individual. A non-exhaustive list of such influences would include

any processes that are in-built (genetic) and found species-wide;

those (cultural and genetic) that might be characteristic of isolated populations;

those (genetic and cultural) of individual personality.

see http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Wiktionary:List_of_protologisms#C

Jay R. Feierman sent:

>

>

> http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2012/06/13/holy-sacred-cow-why-reactions-to-the-exercise-and-depression-trial-go-to-the-heart-of-scientific-controversy/By Hilda Bastian

————————————

Jay R. Feierman sent:

>

>

> http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2012/06/13/holy-sacred-cow-why-reactions-to-the-exercise-and-depression-trial-go-to-the-heart-of-scientific-controversy/By Hilda Bastian