Automatic chemistry

PLOS is pleased to relaunch its Student Blog with this post from Joshua Howgego, a chemistry grad currently in the Science Communications program of Imperial College, London. Please come back to hear more from Josh and other promising writers who will share opinions and experiences while studying a scientific discipline or the communication of science.

Many of the criticisms of science boil down to the fact that the people who do science are only human – they make mistakes, head down blind alleys, look out for their career and hedge their bets. But what if we could make science automatic? It would take all of that unattractive partiality out of the endeavour. But would that be a good thing? Chemistry, perhaps more than any other science, is already becoming automated, and in this post I’ll explore what that looks like and what it could mean.

The most obvious example of how automation is influencing chemistry comes in the shape of Chematica, a map of organic chemistry, published by Bartosz Gryzbroswski earlier this year [1]. The map comprises a series of nodes – actually around 7 million of them – each representing an organic molecule, connected by links representing chemical reactions that can be used to transform one molecule into another. Gryzbroswski’s team have spent years working out the structure of the network.

This is not just any map. It has been called an ‘internet for organic chemistry,’ but (perhaps because I have just moved to London) I prefer the analogy of the London Tube Map. The important thing about this map is that it is a schematic – and that’s exactly what Chematica is. The emphasis is on connections, not necessarily on ‘relatedness’ in the real world. On the tube map stations can look miles apart, but on the surface, they are often much closer to one another than you would think. For chemists it is the habits and traditions of their discipline that sometimes make the connections between chemicals hard to spot. Chematica reveals them.

Because of this, one intriguing use for the map is to identify new routes to medicinally important molecules. For example, if new reaction sequences can be identified which all share the same solvent, they can be performed in tandem, without having to purify the material between steps. On an industrial scale innovations like this could save huge amounts of time, money and effort. Grybrowski reports that Chematica has found new routes to some of the substances that his spin-out company Prochimica makes, offering savings of up 45% on their target molecules.

It sounds impressive, and the reports have certainly made headlines among the chemical community (for example, see this piece by Phillip Ball). But it would be easy to imagine some of the more crusty members of the chemical academe grumbling that the map will take the art out of organic synthesis. Many practitioners of the discipline think of making complex molecules as a bit like chess: planning an attack on a compound takes scientific understanding, sure, but also skill and creative thinking (the final few steps of the challenging organic syntheses are even known among chemists as the ‘endgame’, in chess parlance).

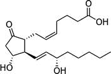

Prostaglandin E2 is a complex molecule with quite a few medicinal uses. There have been numerous inventive syntheses of this compound over the years; one very recently [2].

But some think that automating the process could actually mean chemists have more time to be creative. That is what Craig Butts of the University of Bristol is hoping, anyway. Butts is director of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in the chemistry department at the university. This technique is the the key weapon organic chemists have when trying to work out what the chemicals are that they make in their round-bottomed flasks. The process of acquiring the data is no mean feat, and interpreting it to elucidate the structures of molecules requires expertise. But Butts has been designing a program that will one day, he hopes, make the elucidation of molecular structure by NMR an automatic process.

“Philosophically, I think a lot of chemistry could be automated”, he says. “And I’ve always felt that people shouldn’t spend a lot of time doing something that a computer or automation process can do for them faster, and hopefully better”.

“Even just using automated procedures to confirm that the structure of a compound that you’ve just received from a supplier is indeed what it says on the bottle – these sorts of things are really big in [the chemical] industry at the moment – because they want to minimise the amount of person time it takes to establish a simple fact.” So the theory is that, with fewer mundane fact-finding tasks to grapple with, chemists should have room for more creativity.

And if chemical techniques become easier to use via automation, it should also mean that non-experts will be able to try them out for size. Varinder Aggarwal, a respected synthetic organic chemist, also at the University of Bristol, is working on ways of doing full-blown chemical synthesis which he hopes will one day be so simple to use, that any intelligent person can have a go. He is designing reactions that have inherently predictable outcomes. In a video produced for the university’s new website, he’s candid about why that might be useful:

“Ultimately, if we can automate [our process], it means that people outside of the discipline of organic synthesis will be able to create their own molecules. It won’t just be really hard-core organic chemists who can do that; it’ll be a much broader pool of scientists […] and they’ll be able to include their own creativity, and create something that’s much bigger than what we have at the moment.”

Critics of Chematica might like to imagine a dystopian future where all art is removed from science, and our drugs and plastics are designed by machines. But, in the short term at least, the opposite seems more likely to be true. We are free to choose how we use automation, and – if we make the right choices – its widespread application in chemistry may eventually herald in a new era of creativity.

—

1. C. M. Gothard et al, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51, 7922. (DOI: 10.1002/anie.201202155)

2. G. Coulthard et al, Nature, 2012, 489, 278 (DOI: 10.1038/nature11411)

Josh Howgego spent the last four years peering into round bottomed flasks, working on a chemistry PhD. Now he has turned his hand to writing about science, and is currently studying science communication at Imperial College London. Follow on Twitter: @jdhowgego

Josh Howgego spent the last four years peering into round bottomed flasks, working on a chemistry PhD. Now he has turned his hand to writing about science, and is currently studying science communication at Imperial College London. Follow on Twitter: @jdhowgego

Speaking as a layperson this sounds a liberating development.

[…] First published on The Student Blog, PLoS, 11 December 2012. Link. […]