How Articles Get Noticed and Advance the Scientific Conversation

By Victoria Costello, PLOS Senior Social Media & Community Editor

The good news is you’ve published your manuscript! The bad news? With two million other new research articles likely to be published this year, you face steep competition for readers, downloads, citations and media attention — even if only 10% of those two million papers are in your discipline.

So, how can you get your paper noticed and advance the scientific conversation?

One word: Tweet.

A Tweet (n.) is an online communication of no more than 140 characters (often containing links), transmitted on the public “social network” known as Twitter. When you Tweet (v.), you enter a conversation of Twitter users.

A Tweet (n.) is an online communication of no more than 140 characters (often containing links), transmitted on the public “social network” known as Twitter. When you Tweet (v.), you enter a conversation of Twitter users.

In a PLOS BLOGS guest post, Gozde Ozakinci (@gozde786), a lecturer in health psychology at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, offered an exemplary use of Twitter in a research workflow.

I dip in and out during the day and each time I have a nugget of information that I find useful. I feel that with Twitter, my academic world expanded to include many colleagues I wouldn’t otherwise meet. … The information shared on Twitter is so much more current than you would find on journals or conferences.

Of course, Ozakinci and her Twitter-savvy colleagues are still the minority among academic researchers.

An odd coupling, with baggage

To most scientists, for whom an initial meeting with Twitter is the opposite of love at first sight, this conversation may as well be happening on another planet. At first glance, they find Twitter facile, a time suck, beneath them — and go no farther. Missing from this dismissive view is an understanding of Twitter as a neutral medium for communication (280 mil monthly users) that is quickly gaining currency among a leading edge of researchers who are exchanging science news and information, data files, feedback on articles, methods, tools, jobs, grants and more — across continents and disciplines.

If you are among the uninitiated, and have a research article coming out soon, how might you join them? A priori, if your goals are to exploit this medium for your own ends and advance the larger scientific conversation, some conventional wisdom must be jettisoned.

The first thing to let go of is the quaint idea that your science should speak for itself. Second is the fear, still rife among scientists, that the act of communicating research beyond institutional walls puts your reputation at risk for the “Sagan Effect;” or, in more current pop culture terms, that you’ll become the science equivalent of Kim Kardashian. A recent Google+ Hangout from SciFund Challenge, titled Using Social Media without Blowing up Your Scientific Career, offers testimonials from some real life scientists to challenge this outdated view.

By joining the scientific conversation on social media you’re not exactly breaking new ground. A 2015 PEW poll of AAAS members (scientists and others) found that 47% had used social media to follow or discuss science. Going deeper, in an August 2014 Nature survey, some 60% of 2500 research scientists polled regularly visit Google Scholar (~60%) and ResearchGate (~40%); and, to a lesser extent, Google+, Academia.edu and Linked-in to post CVs and papers — essentially engaging in a one-way form of scholarly communication; talking, not necessarily listening.

Farther ahead on the social media curve is a 13% subset of the Nature group who are involved a two-way conversation with their scientific peers. These scientists describe their use of Twitter, in particular, as a platform to comment on and discuss research that is relevant to their field. Another term for this practice is “micro-blogging.”

If the end game is impact, the way there is engagement

Engagement between authors and readers of research articles comes in many forms, characterized by rising levels of interaction. A potential range is illustrated in this figure from a PLOS ONE study looking at reader responses to 16 articles in the pain sciences disseminated using social media. As the authors point out, the collection of metrics for more complex levels of reader engagement (impact) is still in a nascent stage. For example, a measurement of the number of readers who apply a newly published research finding to clinical practice is currently not available, although it seems likely that a self-interested tech sector will meet this challenge, and meet it soon.

What about my paper?

As a researcher looking for readers, your imperative is more basic. With many more of your peers going to social media to push out their latest work, the status quo of one-way science communication will no longer suffice. Even if all you’re after is readers for your article, it behooves you to use these newly available tools to stand out in a crowded field.

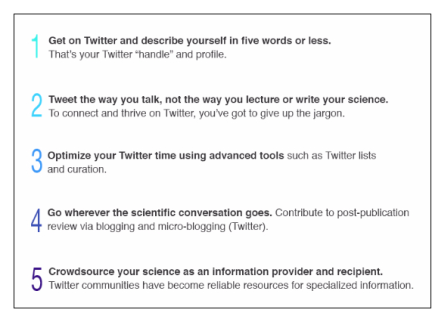

This is where micro-blogging, and Twitter, in particular, come in. Here are five tips to help you join the growing number of scientists and students who are leading their peers to the likely future of scientific communication.

Tip 1. Get on Twitter and describe yourself in five words or less

To get started on Twitter you must choose a “handle” (user name) which sums you up — in 160 characters or less. This can actually be a very useful exercise. What makes your research contribution different from everyone else’s?

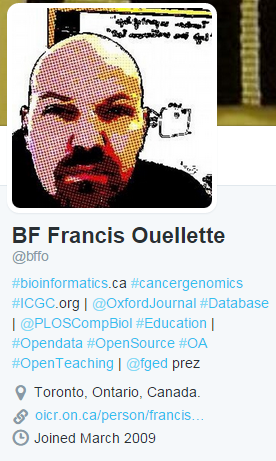

- To create a pithy Twitter profile and find your peers, follow the model of cancer bioinformatics researcher, B.F. Francis Ouellette (@bffo), by coming up with three to five words to describe your work. Use key words; include methods, disciplines and related fields, institutions, journals, diseases or occupations that relate to your science.

- Add a photo of yourself or an avatar but save the pic of you kissing your pit bull, like your passion for artisan beers, for your Facebook or Instagram page. (Most scientists wisely keep their personal and professional social media accounts separate).

A PLOS Biology perspective provides an overview of what social media can do for scientists, with a comprehensive primer on how best to get started, including on Twitter.

Tip 2. Tweet the way you talk, not the way you lecture or write your science

If, like most scientists, you’re a collaborator at heart, use Twitter as a place to share your knowledge; mentor and be mentored; discuss and debate the merits of research. Make your Twitter “voice” reflect your real personality. Keep it casual.

What should you tweet?

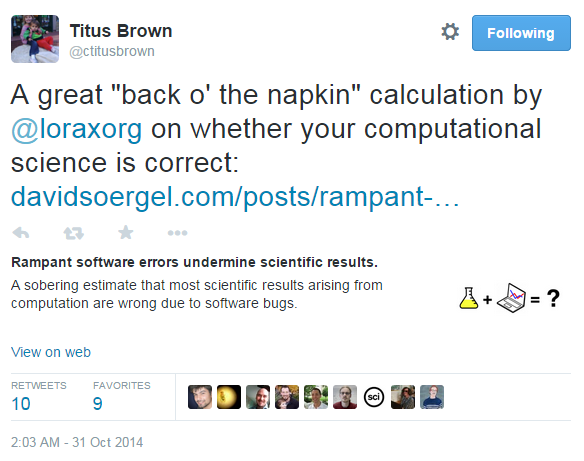

- Recommend links to online content of interest. Say why you’ve singled out that research article or blog post for a mention.

- Ask questions and flag concerns.

- Offer deserved compliments and congratulations to your fellow researchers.

A word on word choices

To connect and thrive on Twitter, you must give up the jargon.

- This tip also applies to the titles of your papers. Turn obtuse technical lingo into plain language, make it catchy, and many more of your peers will click through to read the paper – even those who would have perfectly understood the original title! Here, an author distilled the (not terrible, but terribly long) article title “The Shear Stress of Host Cell Invasion: Exploring the Role of Biomolecular Complexes,” into the tweet below. Got your attention faster, right?

- If your article contains a striking image or figure by all means tweet it too – and not just the cute animals. Even a virus can be a beautiful, especially to your fellow scientists. And, hot off the press, Twitter now allows posting of video clips.

Remember, your immediate goal is to acquire attention for a newly published article. Longer term, you’re after relevance in the ongoing scientific conversation. To track how well you’re doing at both, check out Article Level Metrics (ALMs), which measure impact in terms of views, downloads, comments, citations and media coverage for each of your articles.

Tip 3. Optimize your Twitter time with advanced tools

After finding and interacting with an initial group of your peers by following them, being followed back, tweeting and retweeting items of interest, you’re ready to try some more advanced community and conversation-building tools, including Twitter “lists” and “tweet chats.”

- A Twitter list is an option on your profile settings which allows you to group together colleagues in one easily accessed virtual file. Then you can *Tweet to individuals on this list or turn the name you’ve given it into a “hashtag” such as #PLOSNeuro. For efficiency, track conversations among users of this hashtag using a multiple-Twitter stream monitoring app such as Tweetdeck.

- Cross promote on your blog. If you maintain an individual blog, display your Twitter stream on its home page to facilitate comments and discussion in both places. (WordPress has a widget for this purpose).

- A Tweet chat or Tweet up is a live, regularly-scheduled Twitter conversation typically used to discuss a single topic or paper. For a good model, visit #PubHT, a biweekly Twitter discussion group on public health issues, described in detail in group member Atif Kukaswadia’s (@Mr_Epid) blog post.

The more ambitious social media-minded researcher can try online curation tools – among them Storify.com and ImpactStory.com — to assemble tweets, which they can then post in blogs as topical science stories, conference reports or on altmetrics-based CVs.

Tip 4. Go where the scientific conversation goes

Most authors would probably prefer that readers of research articles say whatever they have to say about their work in the comments section immediately below the article on the publisher’s website. And yet, as discussed above, this train has already left the station; like it or not, the conversation has moved.

In the view of Jonathan Eisen (@phyogenomics), a prolific blogger and tweeter and a long-time PLOS Biology Editorial Board member, formal comments sections will continue to lose any participation they once had.

“I guarantee there are more comments on Twitter about a PLOS paper,” he said.

To become a part of this fast-growing culture of decentralized assessment of scientific research, try using Twitter to share your (abbreviated ) feedback on new articles. Then add a link to the published article — which may or may not contain a longer version of your comment.

Hopefully, Professor Eisen’s prediction isn’t yet a done deal and publishers, including PLOS, will fully rise to the challenge of making continuous assessment of the research a “no brainer” both on and off journal sites.

For its part, PLOS is facilitating scientist-to-scientist communication in discipline-specific communities. These dedicated PLOS pages are run by Community Editors external to PLOS, who are supported by staff and academic editors from the PLOS journals. Community editors crowdsource researcher feedback on previously published articles contained in PLOS Collections, and new research published by PLOS and other non-PLOS journals. This program began in 2014 with PLOS Neuroscience and PLOS Synthetic Biology, with others to be added in 2015. Critiques (comments) on research articles are posted in a community blog featuring original and syndicated posts, with blog posts amplified by real-time micro-blogging from Twitter lists posted on these same pages.

Meanwhile, the Twitter part of this larger scientific conversation is here to stay, no matter where it “lives.” For a model of how Twitter, Facebook, Linked-in and WordPress blogging can be integrated into an academic science work flow, particularly that of early career researchers and students, read this blog post from Stewart Barker, a 1st year PhD student in microbiology at The University of Sheffield.

Tip 5. Use Twitter to crowdsource your science as an information provider and recipient

We start from the premise that the scientific community can reliably be counted on to “root out the rubbish.” Rubbish in this context usually refers to bad science, or misleading interpretations of good research.

In a similar vein, science-based Twitter networks are proving to be rich and reliable sources for rapidly offering and receiving highly specialized information – with questions and answers flowing from scientist to scientist and between scientists and science journalists. For an example of the latter, journalist Seth Mnookin (@SethMnookin) describes crowdsourcing a complex genetics question while on a tight deadline, with help arriving just in time from UCLA geneticist Leonid Kruglayak (@leonidkruglayak).

SciComm ripple effects

The ongoing adoption of Twitter is having a measurable effect on individual scientists in terms of increased productivity and readership, even if the jury is still out on a correlation between Tweets and citations.

Beyond the individual benefits for scientists who incorporate Twitter into their research life cycles, altmetrics researcher (and coiner of the term) Jason Priem, writing in 2011, saw scientists interacting on Twitter as a “revolutionary form of scholarly communication,” one which could “transform centuries-old publishing practices into a much more efficient and organic vast registry of intellectual transactions.”

“Registry” is an interesting choice of words in that it suggests a permanent record. Seemingly transient, the 140 characters you tweet today remain accessible far longer than you might think (Twitter has recognized the value customers place on the ability to recreate their tweeting histories and have made it possible to go back a full seven years – the entire lifetime of Twitter – to find up to 3200 tweets per user). There’s even talk of giving tweets their own Digital Object Identifiers or DOIs. Meanwhile, the Modern Language Association (MLA) provides a standard format for citing a single tweet in an academic manuscript.

Embrace the wider effects. Once you find your voice and engage with fellow scientists via online social networks, you will draw the attention of science journalists with direct access to an international online audience of readers you cannot reach on your own. Fortunately, your needs and theirs are symbiotic: science writers need research news and you can supply it. How likely they are to select your article, and how accurately they interpret the essence and significance of your findings, depend on how widely and clearly you communicate your science — after your research article is published. This is where your institution’s Public Information Office (PIO) can play a pivotal role, especially if you stay involved by checking the press release for clarity and accuracy and by exploiting your own network for outreach.

In the view of many in the broad scientific community, your job doesn’t end there.

In light of the recent PEW poll revealing large gaps between scientists’ and public views on critical scientific issues, many scientists are re-evaluating their individual responsibility to communicate directly with the general public. If, as UK Chief Scientific Advisor Sir Mark Walport recently told a meeting of climate scientists, “Science isn’t finished until it’s communicated,” it follows that scientists’ use of large public social media platforms such as Twitter to explain their science will be increasingly considered a vital part of a researcher’s work flow.

How might the wider adoption of social media impact the entire scientific enterprise? Join the conversation and you’ll be among the first to find out.

A PLOS invitation: no time like the present

If you have an article coming out any time soon, this just may be a Goldilocks moment for you and your research team to take the plunge into Twitter.

To celebrate our recently passed milestone of reaching 70,000 Twitter followers (200K if we include all PLOS journals), PLOS has an invitation for you. If you’ll take a moment now to create your own Twitter account, then follow us @PLOS, we will strive to be among the first to follow you back.

And, while you’re choosing who else to follow, please consider the PLOS journals:

Thank you and we’ll see you on Twitter!

*Thanks to @sharmanedit for pointing out that it isn’t possible to “Tweet to a Twitter list” as this had read previously. Still useful as a Rolodex like file keeping system, I find.