Valentine’s Day Couples in the Animal Kingdom

While humans may be the only ones with a day dedicated to celebrating romantic love, rest assured that the semblance of ‘love’ is alive and well in the animal kingdom too. While ‘love’ in this context may not hold the same meaning we normally think of, animals on land, air, and sea are diligently working to keep their species alive. In honor of them, the PLOS ONE staff has gathered a few of our favorite ‘animal love’-themed research articles to share with you this Valentine’s Day.

Letting People Know You’re Taken, Frog-Style

Image is from Figure 1 of the published article

Letting people know you’re taken can be important, and no one knows this better than the male stony creek frog. The males of this species change color from boring brown to a ‘look at me!’ yellow in a matter of a few minutes during mating (pictured above). The authors of “The Neuro-Hormonal Control of Rapid Dynamic Skin Colour Change in an Amphibian during Amplexus” aimed to determine the hormones behind this color change. Previous studies, showing that stress in this species may trigger the color change during mating, helped the authors narrow down their focus to look specifically at stress hormones. By exposing captured, wild male frogs to epinephrine (also known as adrenaline), testosterone, and a control substance, they were able to determine that epinephrine likely plays a key role in turning the frogs yellow. Based on their observations, the authors hypothesize that the bright yellow color is a signal to other males that they have secured a female, and a way to possibly prevent other males from getting in the way of an all-important mating session.

‘Spur-Poking’ in the Name of ‘Love’

Image is from Figure 3 of the published article

Fighting among males for mates is fairly common in the animal kingdom, but a group of researchers investigated whether there were any evolutionary patterns in snakes exhibiting this behavior. The authors of “Phylogeny of Courtship and Male-Male Combat Behavior in Snakes” looked at 33 male snake courtship behaviors across 76 species, retrieving these details from pre-existing literature. Some of these behaviors included ‘biting,’ ‘tail whipping,’ and ‘spur poking.’ They also note that since snake behavior often goes unrecorded, future data collection is needed. They mapped these behaviors on a phylogeny, an evolutionary map that included 30 species of snakes belonging to the superfamily Colubroidea. After analyzing this comparison, they were able to discern a pattern (see image above) and gain idea of the time period that certain behaviors were introduced to a species. Based on this evaluation, a “head raise with simultaneous downward push” and “spur poking” were some of the earliest attack methods deployed in combat between these male snakes, all in the name of ‘love,’ of course!

Steller Sex: Two Birds of a Feather

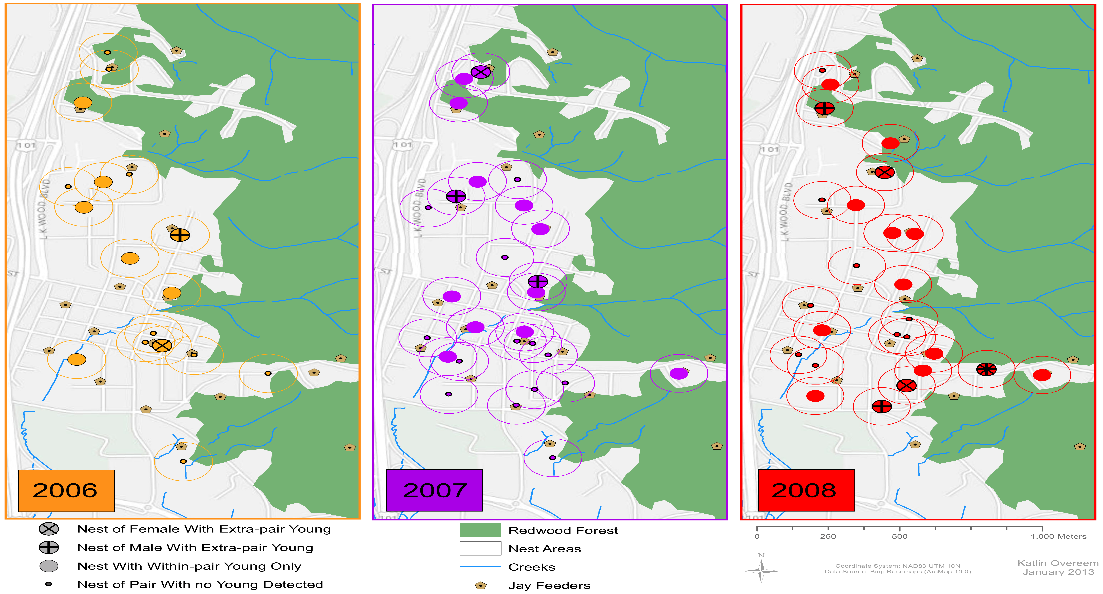

Image is from Figure 1 of the published article

While there are many species of birds that are ‘monogamous,’ many also mate outside social pairs. The authors of “Steller Sex: Infidelity and Sexual Selection in a Social Corvid (Cyanocitta stelleri)” aimed to determine what role male ornamental plumage plays in Steller jay chick paternity. The authors worked with a population of Steller jays in which 25 social pairs (life partners) were known and collected blood samples from the birds and their chicks. They were then able to determine the number of chicks that hatched after extra-pair mating. After analysis, the authors found that 15% of chicks in this Steller jay population were the product of extra-pair mating. Additionally, they found that jays whose male mates had lower quality plumage had more extra-pair chicks, while those whose mates had higher quality plumage had fewer extra-pair chicks. However, a nest full of extra-pair chicks does not go unpunished. Other studies have shown that bird nests with a higher percentage of extra-pair chicks result in less effort toward parental care on the part of the male.

My Sweet Little Dumpling [Squids]: Getting Frisky in Front of Flatheads

Images are from Figure 1 of the published article and Wikipedia

Being a “third wheel” can be an uncomfortable situation, but Nature takes that to another level when a predator “third wheel” approaches two mating creatures. You would think that the presence of predators would put animals on high alert and deter them from mating, but that may not always be the case. Many animals face a trade-off between survival and reproduction, and sometimes reproduction is their most viable option. Female dumpling squid (one pictured above) produce ink to mask their coupling from hungry sand flathead predators, but male dumpling squid do not bother to produce any defense mechanisms when they are mating.

To observe this mating behavior, the authors of “Does Predation Risk Affect Mating Behavior? An Experimental Test in Dumpling Squid (Euprymna tasmanica)” matched fifteen pairs of dumpling squid, and then subjected each pair to three separate predation simulations. The dumpling squid couple and the sand flathead were separated by a clear acrylic sheet with holes in the top, so that they could see and hear one another. The predator was introduced before, during, and after the squid couples’ mating, to observe whether its introduction would interrupt or stop the squids from getting busy. They found that females inked significantly more when a predator was introduced before mating, but the males did not ink. Males would not cease mating to protect themselves because an interruption would mean fewer sperm would be transferred, and he would be less likely to impregnate the female. In addition, predation risk did not influence the squids’ likelihood or duration of their mating. The image above depicts a pair of mating dumpling squid, and you can watch a video of their inking, jetting, and copulation behaviors here:

Reindeer Romance?

Image: The reindeer – Rangifer tarandus – Flickr

Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) may look cute and innocent, but they can be aggressive when it comes to mating. During the rutting season, female reindeer move in large groups either to sample mates, or to avoid harassment from the males—not exactly the most romantic of situations. Often the dominant males will herd the females in a group, rather than follow an individual female, both to act as their protector and to increase their chances of successful reproduction. The authors of “Highly Competitive Reindeer Males Control Female Behavior during the Rut” investigated these behaviors by observing 11 male and 34 female semi-domestic reindeer during the breeding season, tracking and recording their GPS position every 15 minutes, for a total of 3800 recordings. They measured the average number in a group and how long the group remained together, and compared those measurements with the length of the mating season and the social rank of the dominant male, which is established based on several variables, such as a large body mass and antler size. Through this model, the researchers demonstrated that the dominant reindeer males, through herding and other mating-related activities, strongly influence the females’ movement patterns. In other words, the reindeer males were a bit machismo when it came to ‘love.’ The females, however, may not have as much choice in their mating partner—quite a double-standard, and not a very modern romance relationship for this animal pairing!

Moths Love to Mingle

Image: Spodoptera litura – Hang Dong – North Thailand by Ben Sale

In contrast to the female reindeers’ relative lack of choice in a mate, female moths (Spodoptera litura) may be a bit pickier when choosing a mate. The authors of “Female and Male Moths Display Different Reproductive Behavior when Facing New versus Previous Mates” found that female moths can tell if they’ve mated with a male moth before, and they prefer to mate with new partners. Male moths, on the other hand, will generally mate with whichever female is present—in other words, he won’t mind if she’s an old flame. In the study, the researchers played a little moth matchmaker, pairing moths up in boxes in the lab to see if they’d mate with one another. They recorded the mating behaviors of the females when they were exposed to new mates, taking note of their expansion of the pheromone gland to attract a male mate (known as calling), the male’s courtship of the female by fanning his wings around her, and the mating of the two moths. They found that females called earlier and more often when paired with a new male partner, but males courted new and previous female mates the same way. This isn’t to say the males’ wooing techniques were boring by any means—in fact, male moths can create some lovely melodies to serenade their lovers.

We hope you enjoyed exploring the mating behaviors of some of our favorite animals— who knows, maybe you were even able to relate to some of them. Such behaviors show that many animals seem to subscribe to the “all’s fair in love and war” mantra—or at least the males do! Whether you’re “assertive” or not when it comes to love, rest assured there’s probably a member or two of the animal kingdom that has recently behaved the same way. Happy Valentine’s Day from PLOS ONE!

Written by PLOS staff members Tessa Gregory and Kaitlyn Keller

Citations

Kindermann C, Narayan EJ, Hero J-M (2014) The Neuro-Hormonal Control of Rapid Dynamic Skin Colour Change in an Amphibian during Amplexus. PLoS ONE 9(12): e114120. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114120

Senter P, Harris SM, Kent DL (2014) Phylogeny of Courtship and Male-Male Combat Behavior in Snakes. PLoS ONE 9(9): e107528. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107528

Overeem KR, Gabriel PO, Zirpoli JA, Black JM (2014) Steller Sex: Infidelity and Sexual Selection in a Social Corvid (Cyanocitta stelleri). PLoS ONE 9(8): e105257. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105257

Franklin AM, Squires ZE, Stuart-Fox D (2014) Does Predation Risk Affect Mating Behavior? An Experimental Test in Dumpling Squid (Euprymna tasmanica). PLoS ONE 9(12): e115027. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115027

Body G, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Nieminen M (2014) Highly Competitive Reindeer Males Control Female Behavior during the Rut. PLoS ONE 9(4): e95618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095618

Li Y-Y, Yu J-F, Lu Q, Xu J, Ye H (2014) Female and Male Moths Display Different Reproductive Behavior when Facing New versus Previous Mates. PLoS ONE 9(10): e109564. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109564