Satellite Telemetry Uncovers the Tracks of Tiny Ocean Giants

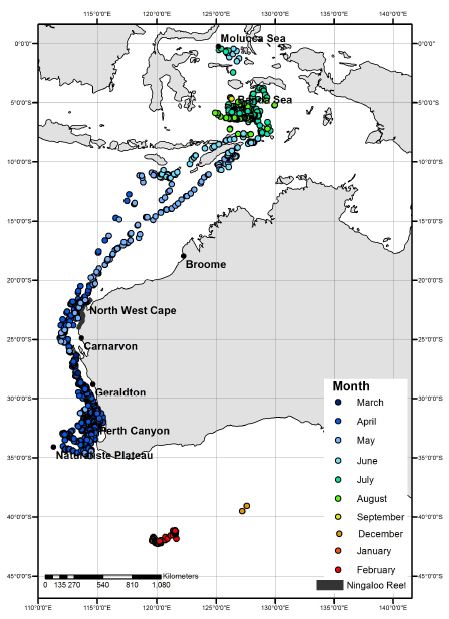

The pygmy blue whale, cousin to the more well-known Antarctic blue whale, has an enigmatic history. Pygmy blue whales dwell in vast expanses of the Indian and southern Pacific oceans, and are a highly mobile species. The species was identified in 1966—although it’s likely to have been confused with its cousin the “true” blue whale prior to 1966—so it’s only in recent years that we’ve been able to catch glimpses of these elusive cetaceans during their migrations to and from breeding and feeding grounds. The researchers of a recent PLOS ONE paper tested out a new method of tracking these whales: satellite telemetry (described below). Using this method, the researchers mapped the migration of pygmy blue whales as they moved from the coast of Australia to the waters of Indonesia. We caught up with author Virginia Andrews-Goff to get some additional details on what it’s like to track these tiny giants.

How did you become interested in pygmy blue whales, and how did you get involved in mapping their migratory movements?

This research was carried out by the Australian Marine Mammal Centre, a national research centre focused on understanding, protecting and conserving whales, dolphins, seals, and dugongs in the Australian region. The work we carry out aims to provide scientific research and advice that underpins Australia’s marine mammal conservation and policy initiatives. We, therefore, have a keen interest in all whales that migrate through Australian waters including pygmy blue, right and humpback whales.

Pygmy blue whales are of particular interest, however, as so little is known in regard to their movements and population status. Large scale movements of whales are particularly hard to study and what we do know about pygmy blue whales we have mainly learnt from examining whaling records. Fortunately, pygmy blue whales were targeted by the whaling industry for only a very short period of time in the late 1950s and early 1960s just prior to the IWC banning the hunting of all blue whales in 1966.

What are the challenges of better understanding whale migration in general?

Large-scale, long-term whale movements are challenging to study as it is impractical to do so by direct observation. Therefore, we need to use devices, such as satellite tags, that can be attached to the whale to provide real-time location information.

What is satellite telemetry and how did it enable your findings?

In this case, satellite telemetry refers to the use of a satellite-linked tag attached to the whale. This tag communicates with the Argos satellite system when the antenna breaks the surface of the water. A location can then be determined when multiple Argos satellites receive the tag’s transmissions. We then receive this location data in almost real time via the Argos website, which allows us to track the movement of the tagged whale.

Based on your tracking, you found that the pygmy blue whales traveled from the west coast of Australia north to breeding grounds in Indonesia. Can you give readers a sense of why they travel this route?

Generally, whales migrate between productive feeding grounds (at high latitudes) in the summer to warmer breeding grounds (at low latitudes) during the winter. The exact reason for this general pattern is unclear, though quite a few theories exist, including to avoid predators, to assist the thermoregulatory ability of the calf, and to birth in relatively calm waters. Because of the timing of this migration, we believe these animals travel to Indonesian waters to calve. Usually it is assumed that whales fast outside of the summer when no longer located in the productive feeding grounds. Interestingly, these pygmy blue whales travel from productive feeding grounds off Western Australia to productive breeding grounds in Indonesia and therefore, probably have the opportunity to feed (and not fast) on the breeding grounds.

You’ve mentioned that pygmy blue whale migratory routes correspond with shipping routes. How does this interaction impact the whales?

Baleen whales (whales that use filters to feed instead of teeth) use sound for communication and to gain information about the environment they occupy. When pygmy blue whale movements correspond to shipping routes, there is potential for the noise generated by the ships to play some role in altering calling rates associated with social encounters and feeding.

Why is it important for us to better understand pygmy blue whale migration, and how does mapping their migratory movements help conservation efforts for this endangered animal?

Our coauthor, Trevor Branch, hypothesised in 2007 that pygmy blue whales occupying Australian waters traveled into Indonesian waters. However, prior to this study, we didn’t actually know that this was the case. As such, conservation efforts relevant to the pygmy blue whales that use Australian waters are required outside of Australian waters too. We can also now gain some understanding of risks within the pygmy blue whale migratory range, such as increased ambient noise from development, shipping, and fishing, and therefore assist in mitigating these risks.

What’s next for you and your research team?

A question mark still remains over the movements of the pygmy blue whales that utilise the Bonney Upwelling feeding grounds off southern Australia. Genetic evidence indicates mixing between the animals in the feeding areas of the Perth Canyon (the animals that were tagged in this study) and the Bonney Upwelling. This indicates the potential for individuals from the Bonney Upwelling to follow a similar migration route to those animals feeding in the Perth Canyon. However, it is also thought that Bonney Upwelling animals may utilise the subtropical convergence region south of Australia. We plan to collaborate on a research project that aims to tag the pygmy blue whales of the Bonney Upwelling and ascertain whether these animals move through the same areas and are therefore exposed to the same risks as the Perth Canyon animals.

We look forward to seeing more from Dr. Andrews-Goff and her team in the future. In the meantime, read more about the elusive worlds of southern Pacific Ocean whales here at the EveryONE blog.

Citation: Double MC, Andrews-Goff V, Jenner KCS, Jenner M-N, Laverick SM, et al. (2014) Migratory Movements of Pygmy Blue Whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) between Australia and Indonesia as Revealed by Satellite Telemetry. PLoS ONE 9(4): e93578. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093578

Image 1: IA19847 Blue pygmy whale

Photograph © Mike Double/Australian Antarctic Division

Image 2: IA19850 Blue pygmy whale

Photograph © Mike Double/Australian Antarctic Division

Image 3: pone.0093578

Image 4: IA19851 Blue pygmy whale off Western Australian coast near Perth, Western Australia, Australia Photograph © Mike Double/Australian Antarctic Division