Beating the Odds: Are Goats Better Gamers than Sheep?

We’re all familiar with the shell game, though many may not recognize it by that name. Popular with street swindlers and sports fans at halftime, it has been annoying those unable to locate which cup the ball is under—most people—as long as anyone can remember. But, what if you were a small ruminant playing a modified version of the game, in which cups were not moved? Seems easier, right? Turns out it may depend on what kind of ruminant you are.

The authors of a recent PLOS ONE article updated this age-old game to find out whether goats and sheep, given information upfront about which cup the food was (or was not) under, could find the food again once the cups were replaced. The ability to connect an experience with an imagined result (“If I see that the cup is empty, the other must have the food!”) is called inferential reasoning, and has been tested in dogs, primates, and birds. Different levels of inferential reasoning, especially between two closely related species, may be linked to differences in the way they search for and find food. A deeper understanding of the different feeding behaviors found in ruminants could shed light on the evolutionary practices that shape these behaviors and help us understand how domesticated breeds have modified their behavior over time to better fit a farming environment.

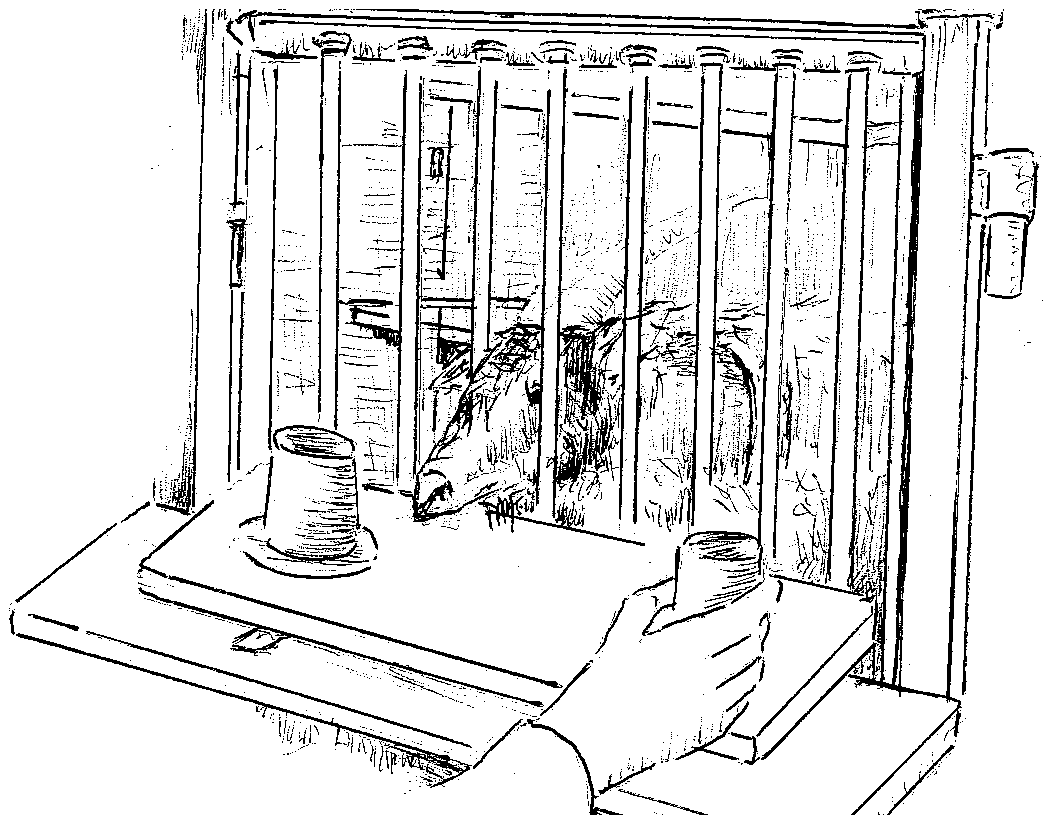

In this study, researchers ran two rounds of testing with slightly different protocols to evaluate how the ruminants’ behavior would change in response to varied amounts of information. They created an experimental set with the animal separated by a series of bars from the researcher and a table (see image above) that held two cups, one with a piece of food hidden underneath. In the first test, researchers lifted one of the following:

- both cups (full information)

- the baited cup (direct information – shown in the video below)

- the unbaited cup (indirect information)

- no cups (no information)

The animal then chose a cup and was rewarded with food if found. The video below shows a sheep correctly identifying the baited cup after receiving direct information on the food’s location.

To minimize the possibility that animals would simply select the cup most recently moved by the researcher, the authors further modified the game for the second round of testing. A set of internal cups was added under each external cup, some transparent and some opaque, allowing the researchers to lift both external cups simultaneously while providing the same amount of information to the animals.

Animals participating in the test were again presented with two cups. Both external cups were removed simultaneously to reveal the inner set, which were one of the following:

- both transparent (full information)

- the baited cup transparent and the unbaited one opaque (direct information)

- the baited cup opaque and the unbaited transparent (indirect information)

- both opaque (no information)

In the same way as in the first experiment, animals were given a chance to select a cup and were rewarded with food if found.

When reviewing the results of all the sessions, the authors found that goats were more successful than sheep at identifying the baited cup when given full or direct information, although sheep also chose the baited cup more often under these circumstances. The second experiment showed that goats were also more successful at finding food when provided with indirect information. In both experiments, sheep did not guess better than chance when shown the empty contents of the unbaited cup or no cups at all, and goats did not guess better than chance when neither of the cups were lifted.

Though several factors varied between species populations used in this experiment—like the time of day experiments were completed, number of animals tested, or history of testing experience in goats—the authors saw no sign of improved performance due to learning in goats, and no differences in motivation as tests continued.

The researchers speculate that the different foraging behaviors used by goats and sheep allowed goats to get ahead in these experiments. Goats are dietary browsers, meaning they are more selective in what they eat and prefer low-fiber foods, like plant stems and leaves. Sheep, as dietary grazers, feed primarily on high fiber foods like grass, and are not at all particular about what they consume. If goats have evolved to be picky, selective eaters, then it makes sense that they might have a better memory for where they saw food in the past, and the insight to avoid an empty cup when they saw one. Future studies on this topic could provide insight on decision making and risk sensitivity in these animals, and give us a glimpse into the minds of a species that can actually beat the odds in the shell game.

Related links:

- Squirrels – Nut Sleuths or Just Nuts?

- Using the Aesop’s Fable Paradigm to Investigate Causal Understanding of Water Displacement by New Caledonian Crows

- Chimpanzees Are Extremely Picky About Where They Sleep (read more here)

Citation: Nawroth C, von Borell E, Langbein J (2014) Exclusion Performance in Dwarf Goats (Capra aegagrus hircus) and Sheep (Ovis orientalis aries). PLoS ONE 9(4): e93534. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093534