Were Ancient Humans Healthier Than Us?

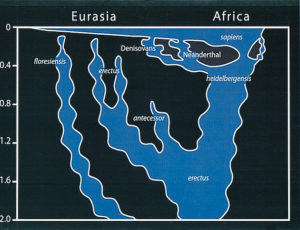

A curious thing happened when researchers at Georgia Tech used modern human genome sequences to look back at the possible health of our long-ago ancestors – they found that while the Neanderthals and Denisovans of 30,000 to 50,000 years ago seemed to have been genetically sicker than us, “recent ancients” from a few thousand years ago may actually have been healthier. Their paper, “The Genomic Health of Ancient Hominins,” is published in Human Biology.

How could that be? Perhaps drugs and procedures that enable us to live with certain conditions also perpetuate gene variants that would otherwise sicken us enough to not reproduce. We pass on those genes and inexorably weaken our global gene pool.

A cheetah with hereditary visual impairment would be weeded out, outrun and not likely to leave offspring. But we humans just use corrective lenses and have kids.

A cheetah with hereditary visual impairment would be weeded out, outrun and not likely to leave offspring. But we humans just use corrective lenses and have kids.

PROBING ANCIENT GENOMES

We’ve come a long way from imagining what life must have been like for ancient humans from just rare teeth and bits of bone. Now sequenced genomes from a sliver of a Denisovan pinkie, from Neanderthal skeletons, and from several sampled tissues of Ötzi the Tyrolean ice man, offer glimpses of past health. Had arrows and wounds not done in Ötzi 5300 years ago, his inherited heart disease might have. He also had brown eyes and type O blood, and would have been lactose intolerant if he’d eaten dairy. Lactose intolerance is the wild type ancestral condition, which didn’t begin to be selected against until adults started consuming nonhuman milk products and suffering cramps.

Joe Lachance, Ali J. Berens, and Taylor L. Cooper of Georgia Tech started out with 449 genome sequences from individuals who’d lived at various times from 430 to 50,000 years ago. The trio compared the ancient genome sequences to a compendium of 3,180 gene variants associated with specific diseases today, ignoring trivial traits and genes carried on the X or Y chromosome. Then they selected the 147 genomes that had more than 50% of the risk gene variants to further analyze. They focused mostly on individuals who lived 2,000 to 9,000 years ago, and categorized each as from a hunter-gatherer, a farmer, or a pastoralist (someone who raises sheep or cattle).

A similar study, one of my favorites, compared Neanderthal DNA sequences to electronic health records from 28,000 modern Europeans. It added to the list of predispositions that Neanderthals might have faced: depression, skin lesions, urinary tract infections, and tobacco addiction.

QUANTIFYING DISEASE RISK

The Georgia Tech researchers used an overall genetic risk score (GRS) as well as 9 specific disease categories.

The GRS included all 3,180 gene variants weighted for the magnitude of their effects. In determining cholesterol level in the blood, for example, some gene variants have enormous effects, such as the mutation that causes familial hypercholesterolemia, and others not so much. The GRS paints a portrait of risk, not necessarily actual diseases.

A high GRS is bad. A value of 82, for example, means the person would have been at greater risk to get sick from risk genes than 82% of modern humans. “How this percentile maps to actual disease risks is likely to be trait-specific. For example, you might only be high risk for a disease if you are above the 90th percentile (think of a liability threshold), with only minimal differences in risk between individuals who are at the 25th and 50th percentiles,” said Dr. Lachance.

The 9 disease categories were allergy/autoimmune, cancer, cardiovascular disease, dental/periodontal, gastrointestinal/liver, metabolic/weight, miscellaneous, morphological/muscle, and neurological/psychological.

The analysis revealed several apparent trends:

The analysis revealed several apparent trends:

• Pastoralists had “extremely healthy genomes” for allergy/autoimmunity, cancer, gastrointestinal ills, and dental health. Farmers and hunter-gatherers were less healthy but about even. Dr. Lachance can’t explain this finding, but suggests that the better health of those who work with cattle and sheep may have been due to exposure to different environments, perhaps like today farm kids have fewer allergies than kids raised in cities.

• Ancient people who lived in the north were healthier. They had better teeth and less cancer.

• The most ancient individuals were less likely to have been predisposed to cancer and neurological/psychological conditions. Maybe they didn’t live long enough to develop cancer or neurological disorders, and therapist records from thousands of years ago are scarce.

• Farmers had the worst teeth. Was it due to the residents of the dental plaque microbiome that formed in response to mashing all those new carbs from grains?

A particularly decrepit specimen was the famed Altai Neanderthal, who lived 50,000 to 100,000 years ago in the Altai mountains of Siberia. Her genome indicates that her parents were siblings, which must have been common when humanity struggled to survive in isolated caves. She had “poor genomic health” and a GRS of a whopping 97%, with genetic signposts of cancer, digestive and metabolic issues, muscle problems, and immune problems. But she had lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

A particularly decrepit specimen was the famed Altai Neanderthal, who lived 50,000 to 100,000 years ago in the Altai mountains of Siberia. Her genome indicates that her parents were siblings, which must have been common when humanity struggled to survive in isolated caves. She had “poor genomic health” and a GRS of a whopping 97%, with genetic signposts of cancer, digestive and metabolic issues, muscle problems, and immune problems. But she had lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

The new work also fleshes out Ötzi: he had gastrointestinal problems and was prone to infection, but was neurologically intact.

A huge caveat to the study is the use of modern genomes as a point of comparison, which was necessary because ancient ones tend to be fragmented in different places. But incomplete evidence was a challenge even when all we had was fossil evidence. Remember the old view of Neanderthals as brown-haired brutes? Thanks to DNA analysis we now know that some of them were redheads.

A huge caveat to the study is the use of modern genomes as a point of comparison, which was necessary because ancient ones tend to be fragmented in different places. But incomplete evidence was a challenge even when all we had was fossil evidence. Remember the old view of Neanderthals as brown-haired brutes? Thanks to DNA analysis we now know that some of them were redheads.

ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESES

The range of genetic risk scores among ancient and modern genomes is about the same, but overall genomic health seems to have improved. That could be due to context.

“It’s important to consider how well an individual’s genome is suited for the present environment,” Dr. Lachance told me, like the effects of a dairy diet on whether or not lactose intolerance becomes noticeable enough to affect reproduction, the currency of evolution. Imagine using a time machine to send someone today back to the distant past, where vision goes uncorrected, influenza is deadly, and tendency to bleed too easily or not fast enough is life-threatening. Gene function always filters through the lens of the environment.

Maybe the blame can’t be placed on our treating diseases that have genetic components to explain why recent ancients may have been healthier. Study design may be a simpler explanation for why the genomes from people who lived a few thousand years ago have a median GRS below 50%, and were therefore seemingly healthier than us. The study looked only at those above 50% – 302 of the 449 ancient genomes fell below that mark.

Consider this: Gene variants that elevated risks of certain diseases, or mutations that actually caused them, might have been stripped from the ancient populations as affected people were too sick to have children, so they wouldn’t even be in the modern genomes to which the older ones were compared. And the healthy pastoralists might have been a sampling error – they contributed only 19 of the 147 genomes.

Dr. Lachance thinks the second possibility – inability to compare full genomes from thousands of years ago to modern ones – the more likely explanation. The truth is out there, but it’ll take more experiments and data to illuminate it.

[…] Source: Were Ancient Humans Healthier Than Us? […]

Hi, Ricky – this is a great article!

By chance, we both came up with a closely related story yesterday:

I put on ScienceBlog.at an article from the Max-Planck-Institute for the Science of Human History (Jena, Germany), entitled “On the trail of historical pestilences: Reconstruction of ancient pathogen genomes of infectious disease”. Besides plague, pre-Columbian origin of TB in America, and leprosy, the authors describe also that Ötzi suffered from a Helicobacter infection.

Best regards,

Inge

Thanks!

Hi, Ricky- this is a great article

One Question

Since there has developed evolutionarily the chromosomal cross-linking, the chromosomal recombination and the genetic repair that happens when one gives a fault in these in addition because it can change in groups of organisms?

Hi, Ricky- this is a great article

The existence of DNA recombination was revealed by the behavior of segregating traits long before DNA was identified as the bearer of genetic information. At the start of the 20th century, pioneering Drosophila geneticists studied the behavior of chromosomal “factors” that determined traits such as eye color, wing shape, and bristle length. In 1910 Thomas Hunt Morgan published the observation that the linkage relationships of these factors were shuffled during meiosis. Building on this discovery, in 1913 A. H. Sturtevant used linkage analysis to determine the order of factors (genes) on a chromosome, thus simultaneously establishing that genes are located at discrete physical locations along chromosomes as well as originating the classic tool of genetic mapping. The revelation that somatic cells also experience recombination did not occur until some years after the discovery of meiotic recombination, when in 1936 that Stern proposed crossovers (COs) between homologous chromosomes to explain patches of mosaicism in D. melanogaster.

do you help me with this question?

Since there has developed evolutionarily the chromosomal cross-linking, the chromosomal recombination and the genetic repair that happens when one gives a fault in these in addition because it can change in groups of organisms?

Thanks

Ricki, I’m a she. Your question isn’t related to my post, so I’m not sure exactly what you are asking. I’m talking about mutation, not recombination. Recombination mixes up existing traits, whereas mutation introduces new variants.

Hi teacher, nice to meet you I´m a biology student in a Colombian university and I need your help to answer this question.

The subject that generates the question is the Mendelian genetics (mitosis and meiosis), about the evolution of genetic cross-linking processes in different groups of living beings; for example, how has the process of geological cross-breeding in reptiles, or amphibians or mammals? and whether such complexity or level of complexity affects intrachromosomal recombination in such organisms; basically at what level has the process of genetic intercrossing occurred over the years? In a simple to complex way? or how has this process occurred? thank for read my question

The subject that generates the question is the Mendelian genetics (mitosis and meiosis), about the evolution of genetic cross-linking processes in different groups of living beings; for example, how has the process of geological cross-breeding in reptiles, or amphibians or mammals? and whether such complexity or level of complexity affects intrachromosomal recombination in such organisms; basically at what level has the process of genetic intercrossing occurred over the years? In a simple to complex way? or how has this process occurred? thank for read my question

Thanks for writing but this isn’t the appropriate place to answer general questions about evolution. Do you have a specific question or comment about my blog post?

Hi good day. I read your blog and I have some questions

Although it is well-known that our ancestors were healthier because they were exposed to different environments, they were given certain defenses by changes in their sequences and therefore survive and reproduce but then why in anomalies such as aneuploidies, where genetic variability occurs, instead of providing more resistance does the opposite occur? or there is the case that aneuploidy or similar event generates more advantages than disadvantages taking into account that we are in a moment where there are major environmental changes. Or are these genetic diseases simply the result of our weakening as a species? Although we know that mutations occur all the time, to what extent these may not favor our survival in the environment. Thanks Mrs Ricki

Aneuploidies (missing or extra chromosomes) are due to random mispairing during meiosis. It just happens.

I have understand that when the mother is reaching a closed age, that is, more than 35 years increases the probability of it happening, I do not know if it is true.

..And can it be said that these events are evidence of our weakening of our species today? or in our ancestors also happened?

The findings can support either the hypothesis that our species is weakening due to disguising disease phenotypes, or that the study was flawed. I quoted the researcher stating that it is more likely the study design, which eliminated the most dangerous alleles from the past because they were selected against.

Yes that’s true. A maternal age effect is for chromosome level events like aneuploidy, but there is a paternal effect for some single-gene mutations.