Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic Cases

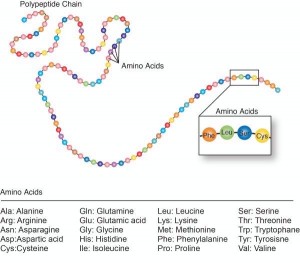

The greatest challenge of majoring in biology in college was mastering the chemical steps that build up and break down the 20 types of amino acids specified by the genetic code. I could memorize the energy pathways with an idiotic mnemonic device – CIA SS F_UCK MY OX – (citrate, isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinyl CoA, succinate, fumarate, malate, oxaloacetate) – and even name the zillions of worms in Zoology 101. But the amino acid pathways really taxed my brain.

The greatest challenge of majoring in biology in college was mastering the chemical steps that build up and break down the 20 types of amino acids specified by the genetic code. I could memorize the energy pathways with an idiotic mnemonic device – CIA SS F_UCK MY OX – (citrate, isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinyl CoA, succinate, fumarate, malate, oxaloacetate) – and even name the zillions of worms in Zoology 101. But the amino acid pathways really taxed my brain.

Had I known that a glitch in a single such pathway could violently twist a toddler’s body and make her smash her head into a wall, perhaps I would have had the context to appreciate what I was memorizing.

Breaking down a biological process into chemical steps has made it possible to prevent symptoms of certain inherited “inborn errors of metabolism” with dietary interventions. The key is early detection.

The story of altering “brain nutrition” to treat genetic disease begins with an astute mother who noticed the odd smell of her children’s diapers. The saga continues today at a small clinic in central Pennsylvania where a dedicated pediatrician and his team are applying biochemistry to save children’s lives.

This post continues a series on my two-hour visit to the Clinic for Special Children in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, in early December. (see Part 1: An Advocate For the Amish At A Very Special Clinic and Part 2: Autism, Seizures and the Amish). I detoured on Christmas to make people mad at me with a post on finding a Neanderthal gene variant in modern Latin American populations.

THE PKU DIRTY DIAPER STORY

In 1931, in Norway, a mother of two young disabled children noted a musty odor to their urine. The father mentioned this to a friend, who told a friend, who was, conveniently, a physician interested in biochemistry. Intrigued, he analyzed the foul urine in a lab at the University of Oslo, with help from the mother, who hauled over bucketfuls of the stuff. The physician, Asbjörn Fölling, identified the problem in the children’s metabolism – later named phenylketonuria (PKU) – and then found it among people languishing in mental institutions. A missing or non-working enzyme blocked their bodies from converting the amino acid phenylalanine into another, tyrosine.

In PKU, excess phenylalanine spills into the urine, the blood, and poisons the brain. In the early 1960s, physician and microbiologist Robert Guthrie, who had PKU in his family, developed what would become known as the “Guthrie test” to detect metabolites in blood (using mass spectrometry) taken from a heelstick shortly after birth.

Because phenylalanine is an amino acid, restricting dietary protein prevents the mental retardation (intellectual disability) of PKU. For a few years, photos of families with PKU showed the eldest children, born pre-diet, sitting in wheelchairs next to their well younger siblings, who’d also inherited PKU but had followed the diet. I had to remove one such photo from my human genetics textbook when a student recognized her aunt as one of the disabled children. The PKU regimen isn’t something off-the-shelf like gluten-free brownies or low-fat yogurt — it’s a complex “medical food” that health insurance covers.

A more familiar diet/genetic disease story is that of “Lorenzo’s Oil” to treat adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), the subject of a 1992 film.

LORENZO’S OIL

LORENZO’S OIL

Lorenzo Odone was born in 1978 to Augusto, an economist with the World Bank, and Michaela, a linguist. In summer 1983, Augusto was sent to the Comorros Islands, off the southeastern African coast, and Michaela and Lorenzo came along. It was an idyllic time, Augusto told me in 2010. “Lorenzo learned French and some Comorrian words. He was a very gifted, precocious child.”

When the Odones returned to the United States, Lorenzo started kindergarten, and soon began to have difficulty paying attention. Then he’d throw tantrums and break rules. By the new year he was falling often, and by spring he couldn’t see. Then blackouts and memory loss started. Soon an exhausted Lorenzo could no longer speak, and then seizures began.

After ruling out a brain tumor, epilepsy, Lyme disease, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, white spots on a brain MRI indicated ALD. The fatty bubble-wrap-like layers around Lorenzo’s neurons were vanishing, but his parents refused to accept the death-by-age-8 prognosis. Instead, they hit the NIH library in Bethesda, and read about a mother in Norway who’d helped develop the PKU diet.

Michaela and Augusto Odone taught themselves enough biochemistry and nutrition to invent a strategy to attack the defect in fatty acid metabolism that was melting the insulation off their son’s brain cells. They discovered that researchers had already tried to treat ALD by restricting the fatty acids that were building up, but it didn’t work. Then in 1986, researchers found that oleic acid sops up the enzyme needed to make the excess fatty acids. The Odones combined oleic-acid-rich canola, olive, and mustard seed oils to create the eponymous mixture, with the help of a biochemist in England.

Lorenzo’s Oil was no mom-and-pop operation. The Odones worked with prominent researchers and the papers reporting clinical trial results appeared in the Annals of Neurology, The New England Journal of Medicine, and the Journal of the American Medical Association. By the time results were in, Lorenzo’s brain was already too damaged for him to respond to the oil, but he took it anyway. Lorenzo Odone died on May 30, 2008. He choked and then bled to death, possibly because of the blood-thinning effects of the oil. It was the day after his thirtieth birthday.

Did Lorenzo live 23 years longer than expected because of the oil? “It could have been his care and the oil. His mother was very careful, but even so, the oil had something to do with it,” Augosto told me, then paused. “But I’m not sure about that.” He died in October 2013, a few months after his final book, Lorenzo and His Parents, was published. Lorenzo’s disease is now treatable with experimental gene therapy (see chapter 8 in my book on the subject.)

AMISH CEREBRAL PALSY IS REALLY GLUTARIC ACIDURIA

AMISH CEREBRAL PALSY IS REALLY GLUTARIC ACIDURIA

Because of those long-ago college classes, “organic” to me has always meant carbon-containing – not a way to grow vegetables. In the organic acidemias/acidurias, too much of an organic acid is in the blood (“emia”) and/or urine (“uria”). Typically too little of an enzyme required to break down a dietary amino acid leads to build-up of whatever the enzyme normally acts on. These conditions affect metabolism of lysine (the amino acid type that the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park couldn’t make, supposedly ensuring their captivity) and the branched chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine).

Many of the derangements of organic acids have tongue-twister names, such as 3-hydroxy-3’methylglutaryl-CoA lyase deficiency, but at least one has the graphic moniker “maple syrup urine disease.”

Anyone can get one of these inborn errors – DNA doesn’t know within whom it mutates. But human interactions can concentrate mutations within populations, especially when people carry samples of a larger gene pool to new communities, as happened with the Amish and Mennonites. In this way, mutations rare in the ancestral European gene pool became amplified in North America.

The need to diagnose and treat glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) led to the founding of the Clinic For Special Children, as detailed in my first post. It’s the most common single-gene disease in the Amish population that the clinic serves, but until Dr. Holmes Morton began investigating it years ago as a young fellow at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the condition had often been mistaken for cerebral palsy. Children died.

A newborn with GA1 appears well for the first few days, but the urine already has high levels of telltale glutaric acid. Then he or she begins to vomit and refuses to eat. The hallmark of the disease is dystonia, the uncontrollable muscle contractions that cause repetitive twisting and writing. Deterioration of the striatum, in the brain, causes the movement problems. The condition progresses to seizures, which often follow a fever. The throat spasms, scoliosis horrifically bends the back, and the child eventually becomes lethargic and comatose.

Today, the symptoms of GA1 are entirely preventable.

The complexity of the biochemistry behind GA1 makes its dietary treatment even more ingenious than those for PKU and ALD. Because of deficiency of an enzyme (glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase) lysine isn’t broken down completely, and an intermediate product of the pathway, glutaric acid, accumulates and enters urine and blood.

The first diet to treat GA1, from 1989, restricted protein to lower lysine levels, but it wasn’t very helpful if symptoms were already present. With the advent of newborn screening for GA1 in 1994, affected infants could be identified (often from urine brought in by midwives) before symptoms began.

Several variations on the low-lysine diet theme were tried. Adding an organic acid called L-carnitine sopped up a bit more of the excess glutaric acid, dropping incidence of brain injury from 94 to 36%. But the disease continued on its course.

Then Dr. Morton discovered a hint in a 1988 paper about bat urine. Healthy fruit bats pee high levels of glutaric acid, just like kids with GA1, but bats don’t develop neurological symptoms because their brains can process lysine. Could glutaric acid trapped in the brains of children with GA1 be causing their motor symptoms?

In 2005 Dr. Morton deduced, from the bat paper, that any treatment for babies with GA1 had to lower glutaric acid in the brain – not just in the blood or urine. And that led to further study of the breakdown pathway for lysine, but in a very specific circumstance – crossing the blood-brain barrier.

To traverse the tile-like walls of capillaries in the brain, lysine is ferried on a protein called a transporter, but competes with the amino acid arginine to grab a spot. When a baby with GA1 spikes a fever, arginine levels in the blood fall as part of the immune response to infection, and more lysine enters the brain – triggering seizures.

Dr. Morton, Dr. Kevin Strauss, and their colleagues reasoned that a dietary formula that cuts lysine by 50% while doubling arginine might block the transporters from binding too much lysine. The situation is a little like something I discovered at the Atlanta airport a few weeks ago.

In 2013, the government investigated a sample of the US population and anointed some of us “low-risk travelers,” harmless enough to breeze through security with our shoes, sweaters, belts and laptops intact and free from interrogation by the Transportation Safety Administration. We special “TSA PreCheck” folk stream towards the scanners past the regular people, and at the last minute, we’re allowed ahead of them – so I’m like an arginine displacing a lysine as we enter the shared transporter. (Note: my group of TSA-approved travelers were all older white women. Profiling?)

Returning to biochemistry, Drs. Morton and Strauss and their colleagues gave the low lysine/high arginine formula to 6 boys and 6 girls, tracking symptoms and blood glutaric acid levels from 2006 until 2011. Twenty-five children born from 1995 to 2005 who took an earlier recipe served as the control group.

The formula worked, and kids with GA1 who take the medical food grow up healthy. “Over 20 years, GA1 was transformed from an unknown disorder that invariably caused disability and early death to a disorder that is recognized worldwide through newborn screening programs and is routinely treated with good outcomes,” said Dr. Morgan. Newborn screening saves lives.

At the Clinic for Special Children, the squares of a beautiful quilt mounted on a wall represent young patients. One patch, from 1989, has what I thought was a grain silo. But it’s a vial of urine, because “that’s how we did samples for inborn errors back then,” Dr. Morton told me. Today targeted mutation analyses supplement diagnoses based on metabolites, to minimize false positives.

THE TRUE FRONTIER OF TRANSLATIONAL GENETICS

Quilts. Sick children in Amish farmhouses. A mother delivering smelly diapers to a biochemist. Parents teaching themselves fatty acid chemistry to create an oil that would heal their son’s brain.

These low-tech stories of treating genetic disease — from the PKU diet of the 1960s, to Lorenzo’s oil from the 1990s, to the glutaric aciduria story and others that I haven’t yet discussed — illustrate the long evolution of tackling inherited disease, one gene at a time. High-throughput, next-generation, massively-parallel, whatever-the-next-buzzword-is exome and genome sequencing have found their niches in diagnosing novel or “unusual presentations” of inherited disease, but for more than 60 years, new treatments have come largely from an understanding of biochemical pathways and medical sleuthing.

Said Dr. Morton, who has won a Macarthur Award and an Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, “Scientists who work as physicians and care for many patients with the same genetic disorder over long periods of time develop a different understanding of genetic disease than scientists who study disease mechanisms in cell cultures. It is often through the daily work of a physician caring for a patient that new opportunities for treatment are realized.” He calls the daily practice of medicine “the true frontier of translational genetics.”

[…] Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic CasesPLoS Blogs (blog)Because phenylalanine is an amino acid, restricting dietary protein prevents the mental retardation (intellectual disability) of PKU. For a few years, photos of families with PKU showed the eldest children, born pre-diet, sitting in wheelchairs next to … […]

[…] PLoS Blogs (blog) […]

This is very interesting about PKU and it was crazy how the mother was concerned by a musky order from the urine.

[…] Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic Cases The story of altering “brain nutrition” to treat genetic disease begins with an astute mother who noticed the odd smell of her children's diapers. The saga continues today at a small clinic in central Pennsylvania where a dedicated pediatrician and his … Read more on PLoS Blogs (blog) […]

[…] Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic Cases The story of altering “brain nutrition” to treat genetic disease begins with an astute mother who noticed the odd smell of her children’s diapers. The saga continues today at a small clinic in central Pennsylvania where a dedicated pediatrician and his …Read more on PLoS Blogs (blog) […]

[…] Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic Cases I detoured on Christmas to make people mad at me with a post on finding a Neanderthal gene variant in modern Latin American populations. …. At the Clinic for Special Children, the squares of a beautiful quilt mounted on a wall represent young patients. Read more on PLoS Blogs (blog) […]

[…] Diets That Treat Genetic Disease – Three Classic Cases […]

third case “Sick children in Amish farmhouses”

reallly intresting about pku