From Gene Therapy to Chromosome Therapy: The New Gets Old as The Old Becomes New

BOSTON This week is the highlight of my year – the American Society of Human Genetics meeting. I headed straight to the gene therapy symposium yesterday, especially since Corey Haas, star of my book on the topic, was just crowned poster boy for the Foundation Fighting Blindness. October isn’t only breast cancer awareness month – it’s also Blindness Awareness Month.

BOSTON This week is the highlight of my year – the American Society of Human Genetics meeting. I headed straight to the gene therapy symposium yesterday, especially since Corey Haas, star of my book on the topic, was just crowned poster boy for the Foundation Fighting Blindness. October isn’t only breast cancer awareness month – it’s also Blindness Awareness Month.

Corey was one of the first to be successfully treated for Leber congenital amaurosis type 2 with gene therapy, in 2008 when he was 8. He’s doing great. He recently got his turkey hunting license, and just entered an essay contest about “Our World, Our Future.” Go Corey!

Alas Corey’s clinical trial team had a greater presence at last year’s meeting, but the celebration of gene therapy’s renaissance continues. The number of people with newfound vision is growing, but it’s much slower going for applications other than the easy-to-reach eye, such as the brain. The reports at the symposium were for preclinical work, early stage clinical trials, and reboots of older trials. Even so, gene therapy seems to have recovered from the setbacks that began in the late 1990s, and is finally moving forward. But perhaps in a few years, it will share the therapeutic space with chromosome-based interventions.

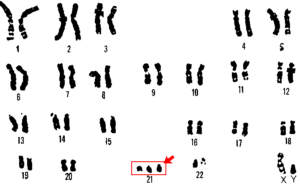

The publication August 13 in Nature of a way to silence the extra chromosome 21 that causes Down syndrome exploded in the media, deservedly. Normally I wouldn’t cover research so thoroughly discussed already, but here at the meeting, immersed in all the large-scale sequencing studies, chromosome silencing stood out. We don’t think so much about chromosomes anymore.

“Gene therapy for single gene defects is gaining ground, but that approach was out of reach for chromosomal disorders. Trisomies involve hundreds of genes, making complex effects difficult to study,” began Jeanne Lawrence, MS, PhD, professor of cell and developmental biology & pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, at the plenary lecture session Tuesday night.

TACKLING TRISOMY 21

Dr. Lawrence’s talk was spellbinding, and her idea to silence the third chromosome 21 of Down syndrome is perhaps the most brilliant idea I’ve heard in my many years of writing about genetics.

French pediatrician and geneticist Jérôme Lejeune discovered the extra chromosome of Down syndrome in 1958. This most common form of the syndrome is genetic but it’s not inherited – the extra chromosome 21 comes from off-kilter chromosome distribution (nondisjunction) that fails to part a pair of chromosome 21s as sperm or egg form.

French pediatrician and geneticist Jérôme Lejeune discovered the extra chromosome of Down syndrome in 1958. This most common form of the syndrome is genetic but it’s not inherited – the extra chromosome 21 comes from off-kilter chromosome distribution (nondisjunction) that fails to part a pair of chromosome 21s as sperm or egg form.

Tuesday night’s talk began with statistics on the prevalence of trisomy 21, which exceeds that of some dozen familiar single-gene disorders combined. “Chromosome disorders account for half of all miscarriages and 1/140 live births. Down syndrome occurs in 1 in 700 births, and 1 in 120 pregnancies in women over age 38, with 400,000 cases in the US. Fifty percent have heart defects, and there’s leukemia, immune and endocrine problems,” Dr. Lawrence told the crowd.

Dr. Lawrence and her team took an approach they call “translational epigenetics.”

REDIRECTING X INACTIVATION

In female mammals, silencing one X chromosome in each cell, early in prenatal development, evens out the chromosomal inequality of the sexes. Another pioneering female geneticist, Mary Lyon, described X inactivation in 1961, also in Nature.

In X-inactivation, a long DNA sequence called XIST encodes a non-protein-encoding RNA that coats the doomed X chromosome, altering the chromatin, methylating the DNA, and blocking transcription. This phenomenon, called dosage compensation, makes up for the fact that a male’s second sex chromosome isn’t a robust, gene-packed X, but the incredibly puny Y, which does little more than make him a he. X inactivation is commonly seen in calico and tortoiseshell cats, who are almost always female. (One in ten thousand calicos is a rare XXY male. I know my cats.)

Many years ago, Dr. Lawrence, who is also a genetic counselor, wondered if XIST could be harnessed to shut off an extra third chromosome. “We took a lesson from nature, silencing the X chromosome.” She was co-author on the 1992 publication, from the group of Carolyn Brown, that showed that XIST RNA coats the X chromosome.

Intentionally silencing a chromosome seemed possible, because translocations that place X chromosome material on an autosome (a non-sex chromosome) also shut off the autosome. If so, redirecting X inactivation to one copy of chromosome 21 would overcome what Dr. Lawrence described as the first obstacle in finding a treatment for Down syndrome: correcting the defect in cells. “We used dosage compensation to lessen the problem of a couple of hundred overexpressed genes,” she said.

The researchers delivered XIST RNA to two sites on chromosome 21 in induced pluripotent stem cells from a boy with trisomy 21. “We thought it wouldn’t work. XIST was too big. The cells might not respond.” But it did work, and the chromosome paint indicating the third copy of the chromosome dimmed and vanished within five days. Eight different techniques confirmed that what seemed to be happening actually was.

Fifteen days after turning off the extra chromosome, 20 to 30% more cells appeared in the cell cultures, including many neural progenitors, providing a very early picture of what goes wrong in Down syndrome.

NEW POSSIBILITIES

Silencing the extra chromosome 21 is a long way from therapy – it would need to affect all relevant cells, which means a very early intervention. But before that happens, the technique will still tell us a lot.

Silencing the extra chromosome 21 is a long way from therapy – it would need to affect all relevant cells, which means a very early intervention. But before that happens, the technique will still tell us a lot.

“The big picture is putting chromosome regulation and pathology together as a research tool. You get two samples, silence one, and compare them, using stem cells so we can study differentiation and development. Then we can figure out the pathways and look for drugs,” Dr. Lawrence summed up. The technique will also reveal which genes on chromosome 21 cause the syndrome, and which control expression of genes on other chromosomes.

The idea of treating Down syndrome other than symptomatically isn’t something people have really thought much about, Diana Bianchi, MD, professor of pediatrics at Tufts University told me as we rehashed the talk the next day. “That’s achievable now,” she said. Dr. Bianchi is exploring an exciting new way to intervene during pregnancy to lessen the effects of Down syndrome, which I’ll save for another post.

So move over gene therapy, there may soon be a new kid on the block. In this age of sequencing everything we can, chromosomes have made a comeback.

Was there any discussion at the ASHG meetings of real or potential roles of the Epstein-Barr virus in chromosomal silencing … and especially its effects on X chromosomes. This question arises because of past research finding by D. T. Purtilo et al on X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome and by S Bocklandt and/or E Vilain on homosexual males.

Dr. Lawrence used zinc finger nucleases. Haven’t heard anything about EBV in this context.

Nice recap Ricki on the matter of X silencing. You always bring clarity and perspective to new ideas in a way that is useful for clinicians and patients alike.

Thanks! Bonnie L. is this you?