Molecular movements drive bacterial signaling

It’s a tough world out there, and just like us, bacteria need to be able to sense their environment in order to respond to it in a way that enhances their chances of survival. And because they’re cozily wrapped in a largely impermeable membrane, they need a system to transmit external information into the cell where it can be interpreted and acted upon.

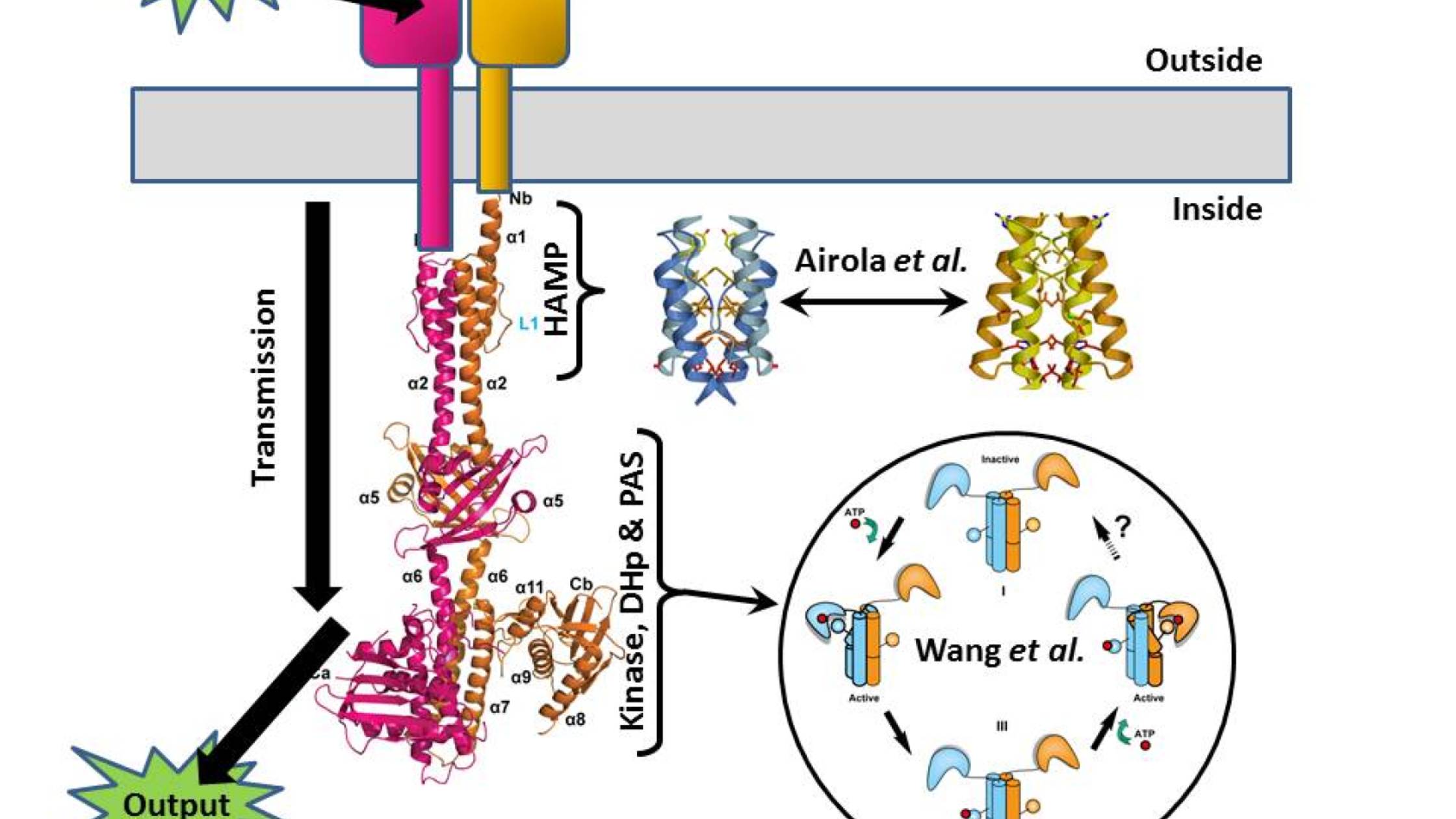

One of the classic bacterial sensory systems is the so-called two-component system (TCS), where one protein (the sensor histidine kinase, SK) transmits chemical information across the membrane, and another (the response regulator, RR) turns that signal into the appropriate action (swimming, biofilm formation, spore formation, and so on). I’m not going to be talking about the RR here (it’s the arrow labeled “output” in the Figure), but we are going to take the SK apart because two papers published in PLOS Biology this month give us important insights into how it works.

The SK has several discernable modules to it. The first is an external domain that receives the input signal from the environment – this might be a nutrient in the case of chemotaxis, or a signal from one of its brethren in the case of quorum sensing. At the opposite end is a histidine kinase domain that generates the output information (in the form of a phosphate tag) to be passed to the RR. And between them lies a transmission system that connects the two. Somehow these all collaborate, enabling the recognition of a tasty morsel – or a bacterial party atmosphere – to trigger the marking of the RR with a phosphate flag.

Just published in PLOS Biology is a paper by Chen Wang, Aidong Han and colleagues that gives us the detailed structure of almost the entire intracellular portion of a pair of SK molecules, namely the transmission and output modules (this is what I’ve used to make the left-hand part of the Figure). And although this is a static snapshot of the system, the authors have been able to use it as a starting point for mutating it to test how it responds to a signal.

The structural study shows the SK to be a long bundle of rods protruding into the cell from the membrane, and their data (including a pronounced asymmetry) suggest that in response to some sort of structural change triggered by the environmental input, a series of tightly coordinated movements occur within the SK molecule pair. A normally straight helix in the DHp region buckles, and the catalytic head of the molecule swings right round, gluing a phosphate onto the rod – this is the signal that’s then passed on to the RR as the output. The authors suggest that the two catalytic heads of the two molecules do this one after the other to fully activate the system (see bottom right of the Figure).

But what is the movement that triggers this pas de deux? This is where the second PLOS Biology paper, by Michael Airola, Brian Crane and colleagues, comes in (together with a Synopsis by Richard Robinson). They look in detail at the HAMP domain – the crucial part of the transmission system that lies closest to the membrane.

There’s been previous speculation that HAMP domains might be able to exist in two distinct conformations, one signalling “on” and one signalling “off”, and Airola and colleagues manage to demonstrate that this is indeed how they work. The presence of a signal outside the cell causes the HAMP domain just inside the cell to click from one state to the other (these are the blue and gold structures either side of the double-ended arrow in the Figure). Niftily, the authors were then able to use mutations to tweak the HAMP domain, changing its sensitivity and even flipping its logic to reverse the “on/off” response.

Together these papers contribute static and dynamic pictures to our understanding of how SKs work, and as the HAMP domain is a key component of tens of thousands of known signalling proteins across the tree of life, the clarification of how they work has potentially wide-ranging significance beyond SKs.

Wang, C., Sang, J., Wang, J., Su, M., Downey, J., Wu, Q., Wang, S., Cai, Y., Xu, X., Wu, J., Senadheera, D., Cvitkovitch, D., Chen, L., Goodman, S., & Han, A. (2013). Mechanistic Insights Revealed by the Crystal Structure of a Histidine Kinase with Signal Transducer and Sensor Domains PLoS Biology, 11 (2) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001493

Airola, M., Sukomon, N., Samanta, D., Borbat, P., Freed, J., Watts, K., & Crane, B. (2013). HAMP Domain Conformers That Propagate Opposite Signals in Bacterial Chemoreceptors PLoS Biology, 11 (2) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001479

[…] weeks ago I wrote a PLOS Biologue blog post that tied together two papers that looked at opposite ends of the signal histidine kinase (SK), a […]

[…] weeks ago I wrote a PLOS Biologue blog post that tied together two papers that looked at opposite ends of the signal histidine kinase(SK), a […]