Debunking Advice Debunked

“Recommendations for effective myth debunking may thus need to be revised”.

One of the authors of this conclusion is Stephan Lewandowsky. He’s also one of the authors of the Debunking Handbook, which made and popularized those recommendations in the first place.

I agree that recommendations about debunking need to be revised. But that’s not because of this study. The evidence was never strong enough to support making that kind of recommendation in the first place. And it still isn’t. This new study doesn’t really shift the evidence base much.

We’re in the same place with debunking advice as we are for so many other widely held beliefs that get debunked:

- Too uncritical acceptance of evidence – especially by people who produced it.

- Not systematically assembling and analyzing enough of the evidence – so that people in the field are only ever looking at a partial picture, picking different studies to make a point or set the scene from one discussion to the next.

- Taking big extrapolating leaps, pushing off from this weak platform.

Communication research is particularly tough. I spent a lot of my time in the 1990s analyzing it. (I was the Coordinating Editor of the Cochrane Collaboration’s review group on communication, infrastructure and publishing for systematically reviewing a body of research and meta-analyzing it.) Because I’m a science communicator, I’m still intensely interested in the work researchers are doing.

It’s inherently hard to study, though, isn’t it? Take how reading things affects people or not.

Who agrees to get into a study like that – and how like real-life is the reading experience going to be? Odds are, you’re skating over this post quickly. Most of the people who clicked on it won’t really read it – and certainly not to the end – and they won’t remember it for long (if at all), except maybe a cartoon. Even if you read it, it won’t be the only thing that might be affecting your thinking on fact-checking and correcting misperceptions by a very long way.

If you were given this post to read in a study, though, where you knew questions would follow, you’d engage with it very differently, wouldn’t you?

Those issues of representativeness of the people studied, artificiality of the circumstances, and isolated “snapshots” from the process of knowledge-building and opinion-forming impose enormous limitations on the strength of evidence. Even the rare longitudinal studies in this area tend to be over quite short periods of time.

So, where are we on that debunking advice?

The Debunking Handbook revolves around “the backfire effect”:

The Handbook explores the surprising fact that debunking myths can sometimes reinforce the myth in peoples’ minds.

The theory here goes, if you repeat the incorrect thing while you’re debunking it, the debunking part mightn’t be remembered, and the mistaken belief could be reinforced by the repetition. Hence the backfire: the belief is more firmly held after the debunking attempt than before.

The new study published in March 2017, by Ulrich Ecker, Joshua Hogan, and Stephan Lewandowsky, was done with 60 undergraduates studying psychology at an Australian university, 42 of them women. (I’ve written about the research on the bias that involves here.)

People were presented with misinformation about a fictional scenario and then corrections in different ways. The fictional scenario was one not likely to have a lot of emotion attached to it: it was about a fire – that’s a standard setting for research in this field.

Everyone was shown 6 scenarios for a short time, which were presented in one of a bunch of different orders. Then there was a bunch of questions, contributing to several scores. The whole episode for the research participant was over in an hour.

60 people, with multiple scenarios, and multiple measures … I’ve written about the potholes on that road here.

Building a knowledge base from studies like this is always going to be limited as a basis for real-life practice recommendations. Value comes from building an understanding of aspects of phenomena, but you would need to test hypotheses generated from this kind of knowledge base – and then show that implementing the recommendations has something like the effect it did in the experimental studies. This kind of research is not itself that test.

Once studies are proliferating, you end up in a jungle with lots of tangled undergrowth. The process of having systematic methods for finding studies, sorting them into categories, critiquing, and analyzing them is like having a map, a torch, a machete, and an aerial view to help you get through it and get it into perspective.

That’s what I want to see here: great systematic reviews that are clear research projects themselves, set up in a way that doesn’t cherry pick studies, that groups types of studies logically, and applies standardized techniques to interrogate the validity and applicability of each study. Despite the importance of this topic, and the proliferation of studies of different types, I can’t find systematic reviews like that.

There have been 2 relevant reviews published this year, but neither is a systematic review and neither interrogates the quality of individual studies. Both involve generators of included evidence as authors of the reviews. Both take that kind of “vote-counting” approach: as in, “we found 1 study in favor, 3 against”. Which is an uninformative method: studies aren’t all equal size and quality. And that kind of method frequently includes apples and oranges, as well.

The first came from National Academies of Sciences (NASEM). It undertook a project to look at the research on science communication, particularly on controversial issues. (Disclosure: I was one of the experts invited to participate in one of the meetings of this project.) But although it’s intended to shape the future research agenda, it didn’t apply a systematic method to do so.

The NASEM consensus report has just under a page on debunking. It includes a different constellation of evidence from that of the Debunking Handbook back in 2011, including some but not all. It has a different constellation again from the second review published this year, in February (PDF), by D.J. Flynn, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler.

The Flynn review is specifically about studies in a political context. It uses a “vote-count” for the sample of 10 studies it includes on the backfire effect. Only 4 of the 9 I could find published accounts of were specifically designed to test whether there is a backfire effect. There is a mix of study types within the studies with different goals, and the quality and reliability of each of the studies isn’t assessed.

What’s the impact of this kind of tangled undergrowth? Here’s an example of a subset of relevant studies from a previous post on this theme, within a broader post about communicating about science in the internet, skeptical age. This diagram shows 5 “apples” and their citation relationship: all randomized trials using CDC information on vaccines to try to debunk myths. (There may be more.)

From my previous post explaining this:

Study A was in 2005 [PDF], B in 2013, C in 2014, D in 2015 [PDF], and E a few months later in 2015. B and E cite A, but C and D don’t. B isn’t cited by C, D, or E. It’s no surprise then, is it, if everyone else doesn’t realize how fluid this situation is?…

[In November 2016] key authors of C and D acknowledge, with the findings of non-vaccine studies, that their conclusions about a backfire effect may not have been justified.

Their initial conclusions weren’t justified in part because they weren’t taking the entirety of the evidence into account, over-relying on their own research. As were the authors of the Debunking Handbook. To their credit, both groups are revising their positions now, but we still don’t have a decent systematic review. (That, I’ve argued, is a serious problem in psychology research as a field.)

None of this means there is no backfire effect. Clearly, the way you communicate can contribute to people doubling down on a contrary belief. And clearly, that’s not inevitable, either. As Neuroskeptic points out, “interesting effects in psychology are variable or context-dependent”.

What we need most now, though, is not yet another individual study to throw on one of the existing relevant haystacks. We need a rigorous systematic review to guide future research – and to show whether or not there is an evidence base strong enough to make any recommendations at all now.

~~~~

What guides my science communication process? That was the subject of a recent PLOS Podcast with Elizabeth Siever. Here’s an infographic PLOS produced based on what I said. If you want to read more about why I believe these things, check out my posts on: dealing with “anti-science”, trust as an antidote, and my personal activist story (with evidence).

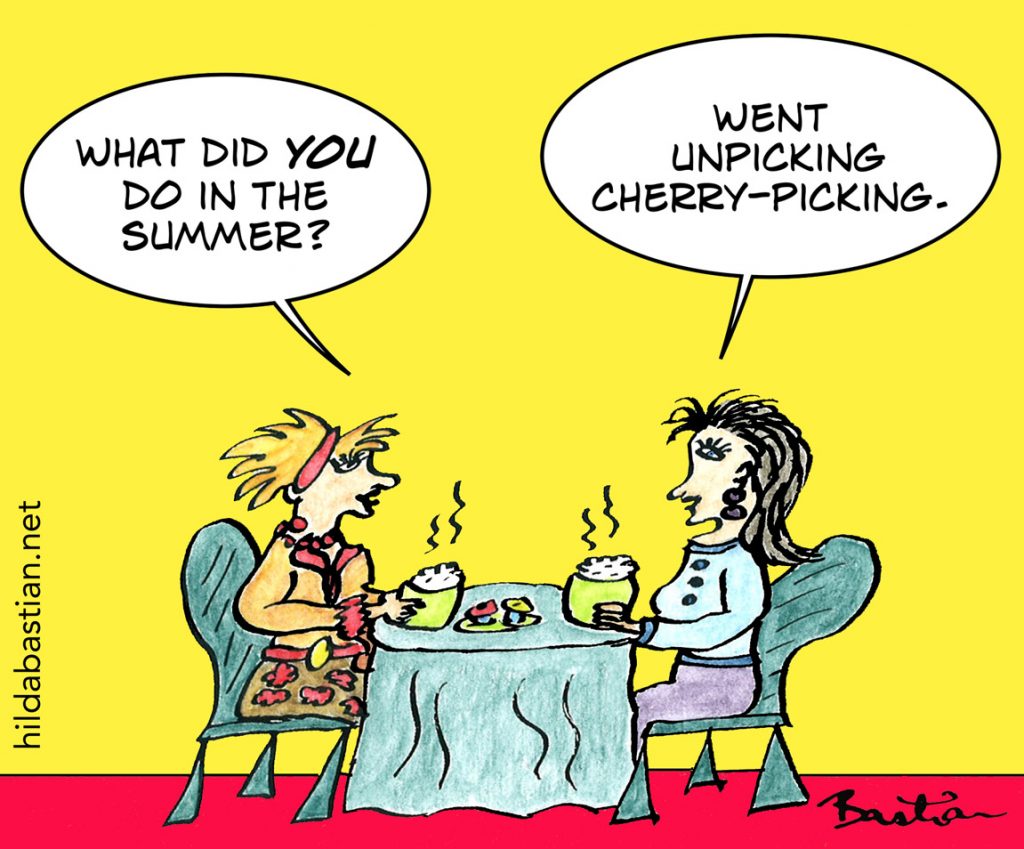

The cartoons are my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.) Behind the choice of words in the cartoon featured at the top of this post:

Debunking: “The science of ‘taking the bunk out of things’,” was coined by novelist and biographer, William E. Edward, in his 1923 novel, Bunk. “Bunk” became American slang for “nonsense” around 1900: short for “bunkum”, for a longwinded, ridiculous speech by a politician trying to get attention in his home district of Buncombe.

Hooey is another American slang word for nonsense from the early 1920s, but the origin isn’t known.

The infographic is from PLOS Podcasts.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.