Pylori Story #2: Journey to the Center of the Stomach

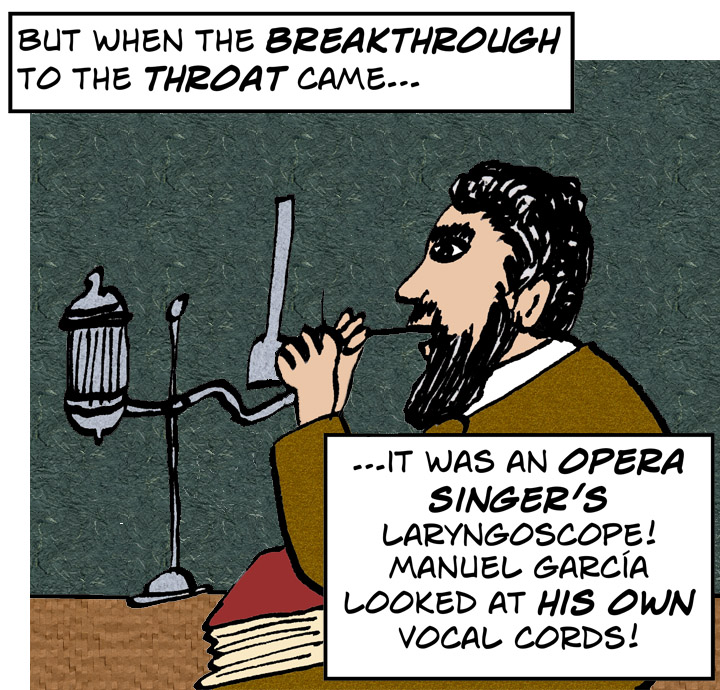

For hundreds of years, doctors battled dim light that burned! Lenses and gadgets that showed too little! But when the breakthrough to the throat came…

Pylori Story continues – click on links below for other installments.

~~~~

Early Steps to Endoscopy to Examine the Stomach

600 BCE: The great Indian surgeon, Sushrusta-Samahita, wrote the first-known description of a tube for examining inside the ear.

400 BCE: In The Art of Medicine, Hippocrates describes using a speculum into the rectum to examine hemorrhoids.

300 BCE: Greek physician, Oreibasiosis, reported a technique with an instrument to look into the throat.

1000: Abu-al-Qasim was a surgeon from Spain who authored a 30-volume medical encyclopedia called Al-Tasrif (The Method), is considered an important figure in pre-modern endoscopy. His techniques examined inside the ear and the urethra.

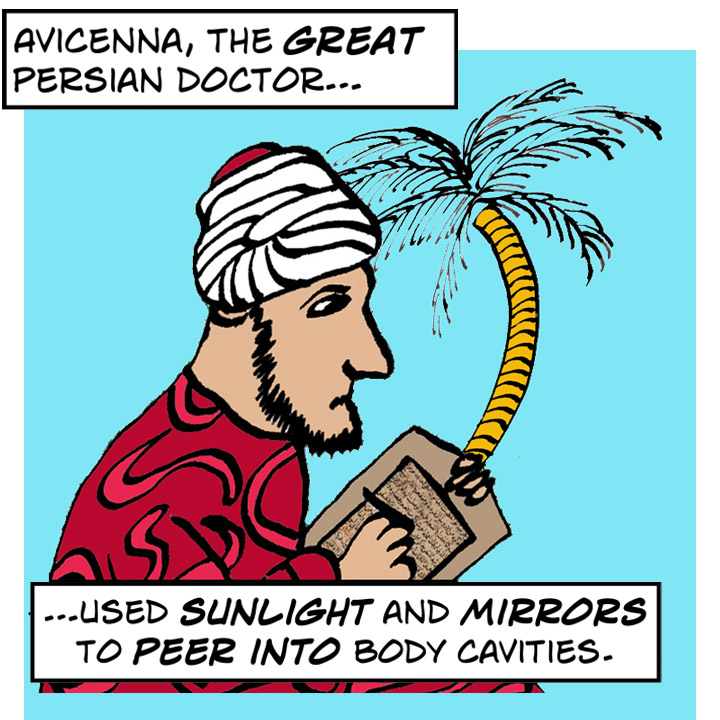

1000: In Persia, mathematician Ibn Sahl worked out refraction of light, pointing to the way to focus light. The great physician, Avicenna, marked the turning point: he used reflected sunlight on polished mirrors to examine the vulva and cervix.

1021: In Basra, al-Hasan Ibn, wrote The Book of Optics, which broke ground for the development of lenses.

1500: In Italy, Gerolamo Cardamo invented a mechanical lamp for examining body cavities.

1550: Giulio Cesare Aranzio used the principles of camera obscure to illuminate the nasal cavity. He filled a glass balloon flask with water, in front of shuttered windows opened enough to let in a beam of sunlight to reflect.

1710: From Germany, Johann Michael Conradi published The First Optical Instruments as Allegorical Depiction, a key text in the development of optics. It includes most of the individual non-electrical components needed to make a endoscope.

1729: Archibald Cleland in England used a wax candle with a device to view inside the nose.

1780: Samuel Vogel in Germany was the first person to report visualizing the eardrum in a living person, using a mirror and sunlight.

1780: L. Spallanzani in Italy described inserting a metal tube into the stomach of a living animal.

1806: A big leap forward came when German Philipp Bozzini published his paper on the “Lichtleiter” – his invention of a “light conductor” to view internal organs. He demonstrated it in Frankfurt. It was the first internally lit device – a candle and angled mirrors inside a case, with a speculum.

1829: Guy Babington in London made a device that could be used with one hand. He used a dentist’s mirror and a tongue depressor, with a second mirror held in the other hand – and sunlight as the source of light.

1854: Manual Garcia, a Spanish opera singer who was then a singing teacher in London, demonstrated his method for indirectly viewing his own larynx at The Royal Society. It is generally regarded as the first laryngoscope. It used one dentist’s mirror, with another held by hand, and sunlight. (Horace Green from New York City later became the first person in America to use a laryngoscope.)

1858: Johann Czermak from Czechoslovakia used a concave mirror and lamp to concentrate light. He had learned basic techniques from Ludwig Tuerde in Vienna. Czermak demonstrated his method at the Viennese Medical Society, and was the first person to take a photo endoscopically: he photographed his own larynx.

1865: Francis Cruise in the US developed an operative endoscope with instruments for urological procedures like emptying the bladder. But the damage caused by over-heating were still not solved.

1866: The problem of dangerous heat from light sources was on the way to being solved when Julius Bruck, a dental surgeon from Breslau in Germany, encased galvanized wires in a glass cooling system. He called it a galvanscope.

1868: Adolf Kussmaul from Freiburg Germany used a urethroscope for light, a 47mm long tube that was 13mm wide, and a speculum, to get to the bottom of sword swallower, Iron Henry’s, stomach.

1877: Maximilian Nitze debuted his cityscape in Berlin. It had internal light and a lens system that expanded the field of vision. It had a mini-microscope, with 3 lenses, and a cooling system. In 1879 he made an esophagoscope and in 1888, he added a miniaturized electric bulb to his devices.

But endoscopy didn’t become a viable proposition for the stomach until after World War 2.

1947: Schindler and Cappell reported on experience with a semi-flexible gastroscope.

1957: Hirschowitz developed the first flexible gastroscope with fiberoptic cable that could see around corners – he tested it on himself.

1976: Lutz, Cappell, and Rosch demonstrated passing a miniature echoprobe though a gastroscope to get sonographic images of the stomach.

In the 1980s, gastroenterological endoscopy took off, becoming the mainstay of gastroenterology practice.

Bibliography:

Cappell MS, Wayne JD, Farrar JT, Sleisenger MH. Fifty landmark discoveries in gastroenterology during the past 50 years: a brief history of modern gastroenterology at the Millennium: Part I. Gastrointestinal procedures and upper gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 2000; 29: 223-263.

Cotton PB. Fibreoptic endoscopy and the barium meal – results and implications. Brit Med J 1973; 2: 161-165.

Peery AF et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 1179-1187.

Sivak MV. Gastrointestinal endoscopy: past and future. Gut 2006; 55: 1061-1064.

Spaner SJ, Warnock GL. A brief history of endoscopy, laparoscopy, and laparoscopic surgery. J Laparoendoscop Adv Surg Tech 1997: 7: 369-373.

The comic in this post is my own (CC-NC-ND-SA license). (More of my cartoons at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.) With apologies for the limited resemblance to the real people depicted!

The cartoon of Avicenna includes a snip from his Canon, from the Yale Medical History Library, via Wikimedia Commons.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.