Science and the Rise of the Co-Authors

Physicists set a new record this year for number of co-authors: a 9-page report needed an extra 24 pages to list its 5,154 authors. That’s a mighty long way from science’s lone wolf origins!

Cast your eye down the contents of the first issue of the German journal, Der Naturforscher, in 1774, for example: nothing but sole authors. How did we get from there to first collaborating and sharing credit, and then the leap to hyperauthorship in the 2000s? And what does it mean for getting credit and taking responsibility?

Some say that specialization led to scientific collaboration. But Beaver and Rosen argue that increasing power and funding professionalized science – collaboration and complexity followed.

That happened in France first, they argue. Science gained an influential place in society during the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, using state funding “to legitimize and institutionalize itself on a grand scale”.

Beaver and Rosen tracked the earliest days of authorship using 10% of the citations in the 16-volume Reuss Repertorium index of the journals of scientific societies in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Very few of those 2,101 citations had more than 1 author (47 citations, 2%) – and of those that did, just over half were French. Even this low number might be an over-estimation. I tracked down the citation Beaver and Rosen point to as the first with more than one author. It’s the one on the left in the snapshots below. You can read that 1665 paper here. This is one person reporting observations from multiple scientists, not work jointly reported.

On the right, is a snapshot of a paper pointed to as a landmark in scientific collaboration. It’s by mathematicians Felix Klein and Sophus Lie in 1870, and it’s definitely joint work. (You can read about their friendship and work together here.)

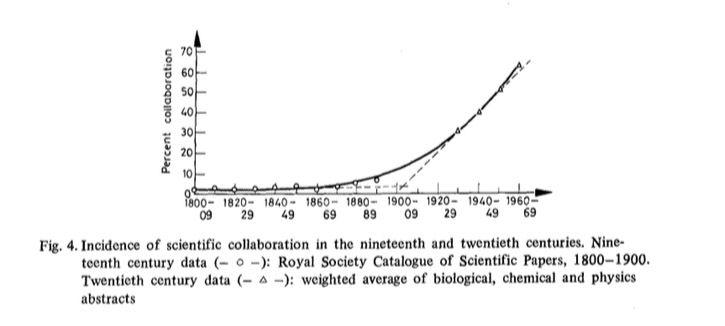

By 1900, about 7% of papers in biology, chemistry, and physics had co-authors and the boom of teamwork had begun (according to Beaver and Rosen’s analysis of the Royal Society catalog). By 1960, it was around 60% of papers. And now it’s the norm in most parts of science, although single authorship is still common in some areas.

The rise was partly because of increased collaboration and partly because of acknowledgment of colleagues’ contributions – there was probably far too little of that previously. Under-crediting of contributors didn’t just go away, though. Meanwhile, we have careened wildly in the opposite direction, too. The bylines of scientific articles are riddled with ghosts and guests who contribute nothing but their name. And the roles that can lead to a place in the line-up have been growing higgledy-piggedly.

By 2000, the average number of authors per paper in medical journals was seven. Hyperauthorship – more than 50 or 100 authors – is a creature of the 21st century, mostly in the physical sciences and biomedicine. Although “mega-authorship” is led by physics, the first paper to go past the 1,000 author mark was a drug trial in 2004. The aptly named MEGA Group blasted the previous record with more than 2,400 co-authors.

A by-product of swelling authorship is diffusion of responsibility. That hit with a thud in 1981. That’s when junior scientists with suspicions about a Harvard researcher, John Darsee, finally laid hands on proof of his fraud – scraps of discarded fake data in a trash can. Dozens of retracted papers over a 14-year period later, co-authors denied responsibility. The editor of one of the journals, Arnold Relman at the New England Journal of Medicine, minced no words about this: scientists can’t happily take credit, but no responsibility.

The incident spurred the collective of medical journal editors to define authorship and responsibility. After years of thunderous debate and unresolved divided opinions, here’s where those guidelines stand today: “Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved”.

That debate in the early 1980s also saw the emergence of specifying contributions to an article – along the lines of credits in movies.

Edward Huth, editor of the Annals of Internal Medicine, proposed it in 1986: “This procedure might reduce the number of abuses by at least forcing application of some kind of criteria”.

A decade later, JAMA’s Drummond Rennie, Veronica Yank, and Linda Emanuel developed the idea in depth, pushing for at least one named guarantor for the article too.

Rennie hit on lots of weak spots in the way authorship emerges, and how unexamined this is, given its pivotal impact on careers and science. He pointed out that while many scientists have strong convictions about what the order of authors means, it “is highly idiosyncratic, and differs even among scientists in the same discipline. If scientists are trying to convey information to the reader by the way their names are ordered, they are using a method akin to sending smoke signals, in a secret code on a dark, foggy night”.

There’s a badge system now for all science, built on the medical journal editors’ descriptions of contributions to articles – some of which they say justify authorship, while others don’t. Liz Allen and colleagues introduced the idea in Nature last year. The badges are explained here by Amye Kenall at BioMed Central.

I’m pretty dubious about this. It’s a quantitative approach to trying to get more qualitative, that seems to me likely to create new inflation problems. Whether further operationalizing contributorship will help is questionable. It would be wonderful, though, if it went some way to increasing the value placed on the contributions of people who aren’t the first or last author. But as Barry Bozeman and Jan Youtie point out that so far, the contributorship route hasn’t been shown to make much difference to serious problems.

Bozeman and Youtie’s article is important reading (behind a paywall – grrr!). They get to the heart of the issue – the need that Tim Albert and Elizabeth Wager, writing for COPE [PDF], describe as encouraging a culture of ethical authorship.

Bozeman and Youtie show that an underlying problem is that we still don’t have solid norms for the process of deciding authorship, and it’s pretty much team-dependent. Decision structure problems arise “because one or more of the authors, usually the most senior one, assumes tacit agreement and consensus when there is none and then decides on co-authoring with little or no discussion” – as well as suppression of dissent, groupthink, squeaky wheels, and what they call “the jackass factor”. Power dynamics are central, and until we understand and tackle that, some people will continue to “exploit their friends and also those who are in less powerful positions than themselves”.

Authorship practice remains astonishingly murky. All science’s incentive problems converge in it and feed from it. It deserves more care.

~~~~

UPDATE 5 January 2016: Resnik et al published a survey of authorship policies at a random sample of 600 journals. They are fairly typical now for biomedical and social science journals, although not so much in physical and other sciences. But asking for contributorship and acceptance of accountability isn’t common.

The cartoon in this post is my own (CC-NC license). (More at Statistically Funny and on Tumblr.)

The photo of the last page of Leonhart Fuchs’ book on medical properties of plants, De Historia Stirpium (1542), comes via Wikimedia Commons and the Wellcome Trust: woodcut self-portraits of/by his illustrative collaborators, ‘Heinrich/ Heinricus Füllmaurer’, ‘Albertus Neher’ and ‘Ditus Rodolph Spectle’. More about De Historia Stirpium here, and more about Fuchs (one of the “founders of botany”, after whom Fuchsias are named).

The 2 early co-authored reports are:

- Robert Hook, Henry Oldenburg, John Dominique Cassini, Robert Boyle. Of a permanent spot in jupiter, by which is manifested the conversion of jupiter about his own axis. Philos Transact 1 (1665): 143-145.

- Felix Klein, Sophus Lie. Deux Notes sur une certaine Famille de Courbes et de Surfaces. Comptes rendus 70 (1870): 1222-1226.

“Figure 4. Incidence of scientific collaboration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries” is from D. deB. Beaver and R. Rosen. Studies in scientific collaboration part III: professionalization and the natural history of modern scientific co-authorship. Scientometrics (1979): 231-245.

“The End” – clip from Josef Von Sternberg’s, The Blue Angel (1930) via Internet Archive.

* The thoughts Hilda Bastian expresses here at Absolutely Maybe are personal, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.